Sermons

Words – Ancient and New

January 23, 2022

Third Sunday after Epiphany/ 23rd January 2022

It’s been said that Presbyterians are people of the book and of books. We certainly are a wordy bunch of Jesus followers. Words matter to us. The words we use to articulate our understanding of God shape our faith and inform how we live. God created the world using words. The hearing of God’s word delights the heart, leads us into praise and worship, stirs something new within us, and causes us to act. Jesus, the Word made flesh (Jn. 1:14), used the words of Isaiah to begin his ministry. And, so, we see how Scripture continues to work, an ancient word becomes, with the help of the Holy Spirit, a new word, and our lives and the world are transformed.

This week’s lectionary holds together these two texts, two moments of significance that both center around the reading and the hearing of scripture. The Nehemiah text recalls the time when the Book of the Law, that is, the Law of Moses, the Torah, was read to the people after their forced exile. God’s people had returned to Jerusalem and rebuilt the walls. Instead of throwing a party, the first thing the people asked for was to hear the Torah read to the people. “All the people gathered before the Water Gate…” (Neh. 8:1). The Water Gate, a central, public space, not the temple, but in the square, at the center of their common life, that’s where the Word was read and heard. The “ears of all the people were attentive to the book of the law” (Neh. 8:3). All the people. All the people. Over and over, Nehemiah tells us that this was a shared, collective experience, experienced together. The hearing then moved them to praise, to worship; they lifted their hands, bowed their heads, and worshiped with their faces to the ground (Neh. 8: 6). “Amen, amen,” they cried. Yes, Yes, and Yes.

Fast forward to Nazareth. Inside the synagogue, we find another public, communal experience, now on the Sabbath. In Luke’s Gospel, the Living Word begins his ministry in Nazareth reading scripture, and not just any text. He’s reading from the Isaiah scroll, and just not any text, but these words: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor” (Lk. 4:18). God’s jubilee.

According to Luke, when Jesus was finished reading, he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. Sitting down, Jesus does something bold and daring—and otherwise inflated and arrogant but for the fact of who he was—says, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Lk. 4:21). Jesus claimed for himself and his mission the prophetic stance of someone like Isaiah. Jesus says that this mission will now be embodied in and through him. The Spirit of the living God is upon him and empowering him to act on God’s behalf. And then that same Spirit sends him into the world, calling disciples to follow where he leads. To be a follower of Jesus of Nazareth, to be a disciple, to bear the name “Christian” means we, too, are guided by the same Spirit who anointed Jesus, led by the same Spirit-anointed Jesus, led by the same Holy Spirit who continues to speak through the pages of scripture and calls us to offer a liberating word.

In both settings, it is the reading of scripture that mediates the voice, the presence, and the vision of God to God’s people. Ancient words, first spoken centuries ago, thousands of years ago for us, can be taken up by the Spirit to become a new Word, a transforming Word, a Word that is both old and new at the same time, new because it is spoken and heard by us, by you and me, in this time. In both settings, God’s Word is not heard privately. It’s heard among “all the people.” Scripture is best read, heard, studied, and lived in community, in a public space. When that happens, we are changed, the community is changed and transformed. Scripture read and heard in the public square can be a radical act of grace, healing, justice, and change. Whether it’s studying scripture in a small group or scripture heard here in worship and preached, we must not underestimate the power at work here to change and transform us. A church—a people—is formed and reformed by reading, studying, hearing, and preaching of the Word, and then enacting, embodying the Word.

That’s the power of God’s Word. That’s what God’s Word can do. I’m not talking about any words, but the Word, and by Word, I don’t mean the Bible. I’m talking about the Word—the creating, redeeming, sustaining, life-giving Word that is God, the God who speaks, the God who said, “Let there be….,” and there was (Gen. 1:3). I’m talking about the God who spoke in the beginning, who spoke and caused the beginning, and spoke the universe into being. The same God is still speaking and still creating new beginnings. The Divine Voice is dynamic and purposeful and continues to act and move and shape us. The Divine Voice spoke to Isaiah, and Isaiah listened to the Word, and the Word turned him into a prophet. God told Isaiah, “My word shall go out from my mouth: it shall not return to me empty, but it shall accomplish that which I purpose, and succeed in the thing for which I sent it” (Is. 55:11). And then, in God’s good time, the Word became flesh, and lived among us, “full of grace and truth” (Jn. 1:14), and we have been forever changed. That’s what the Word can do.

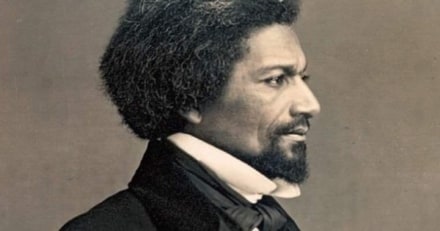

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey knew what the Word could do. Born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay, in Talbot County, Maryland, around 1818, no one knows for sure. In early March 1826, Frederick received word that he was being sent across the Chesapeake to Baltimore to live with Hugh and Sophia Auld in Fells Point. Baltimore, one of the most thriving and growing port cities in North America, was the largest trading center for tobacco, wheat, flour, coffee, and, sadly, enslaved Africans. Around that time the city had 80,000 people: 60,000 whites, four thousand enslaved blacks, and more than fourteen thousand free blacks—the largest concentration of free persons of color in the United States.

Frederick couldn’t read, but he was bright and intellectually curious. He was obsessed with words and not just any words. Sophia Auld read aloud from the Bible as Frederick slept under a table near her feet. He became obsessed with the Bible. He wanted to read, and Sophia started to teach him privately. When Hugh discovered this, he rebuked her and told her to stop because literacy was unlawful in Maryland for enslaved blacks. Hugh said, “Learning would do [Frederick] no good, but probably, a great deal of harm—making him disconsolate and unhappy.” And if Frederick was taught to read the Bible, Hugh said, “there will be no keeping him.” It would “forever unfit him for the duties of a slave.”[1]

Frederick went to Wilk Street Methodist Church with Hugh and Sophia. He heard the sermons and the stories. He heard from the pulpit that “All men…bond and free” were sinners needing redemption. Frederick was befriended by a black lay preacher, Charles Johnson, who taught him to pray and helped awaken his heart and led him to confess “faith in Jesus Christ, as the Redeemer, Friend and Savior.”[2] After that, Frederick said he saw the world “in a new light.” He said he “loved all mankind—slaveholders not excepted; though I abhorred slavery more than ever. My great desire now was to have the world converted.”[3] Frederick developed an insatiable hunger to hear more from the Bible. And he wanted to read the Bible for himself—and so he secretly taught himself to read.

In 1833, Frederick was sent back to the Eastern Shore (because of a feud between Hugh and his brother, Thomas) and forced to live in a cruel, sadistic setting. Around this time, Thomas had something of a “conversion” at a camp meeting revival in St. Michael’s. But he continued to beat his slaves brutally, including Frederick and didn’t see the hypocrisy in that. Frederick saw it and felt it; he came to see the hypocrisy in the entire “Christian” slaveholding universe.[4] Knowing the Bible, he knew what scripture says about redemption and liberation for all God’s children.

Frederick eventually escaped from slavery, headed north, changed his surname to Douglass, and became one of the nineteenth century’s greatest writers, orators, humanists, and Christian prophets. In his outstanding biography, historian David W. Blight argues that Douglass became “one of abolition’s fiercest critics of proslavery religious and secular hypocrisy.”[5] Douglass felt in his soul and body the “blood-chilling blasphemy,” he said, at the heart of proslavery piety, these “professedly holy men” who owned his body and tried to own his mind.[6]

And it was the Bible, but not just the written words, but the witness of scripture, the voice that comes through the text, God’s world-creating, world-judging, world-renewing, radical, liberating, life-giving Word carried by the words of the text, ancient and new, which told him who he was, who his neighbor was, and gave him a vision of what God desired for all people.

Near my desk in the study, I have this quote from St. Augustine (354-403). It comes from his classic work, Confessions. Augustine writes, “O Lord Thou didst strike my heart with Thy Word and I loved thee” (X.6).

This is what the Word can do and does. There is a direct line from the Law and the prophets, from the prophetic voice of Isaiah to Jesus of Nazareth to countless other prophets throughout the centuries, to Frederick Douglass, to preachers, writers, poets, reformers, to scientists, visionaries—heck, anyone anointed by the Spirit of God to bring good news, good news to a world that desperately needs to hear it, especially the marginalized, oppressed, and poor. This is what God’s Word continues to bring to the world. The Word brings liberation. What we say, what we preach, how we live, how we treat our neighbors and strangers, all that we do, can be proclamations of liberty that help to release people from whatever binds them. We offer insight and light to help people see and see clearly, help people who are blind come to see God’s desire to liberate all people and usher them into the jubilee and joy of the Lord. Yes, the Word brings liberation from all that binds and holds and holds back God’s people. And then the Word liberates the heart to sing for joy, frees us to lift our hands in praise, and fall with faces to the ground lost in wonder, love, and praise—and the world is forever changed and transformed!

——————————————————–

[1] Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom, originally published in 1855. Cited in David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 39.

[2] Douglass, cited in Blight, 52.

[3] Douglass, cited in Blight, 53.

[4] Blight, 58.

[5] Blight, 59.

[6] Blight, 59ff.