Sermons

Making the Turn

January 24, 2021

Third Sunday after Epiphany/ 24th January 2021

Consider Jonah—God’s reluctant prophet. God sent him to cry out against the “wickedness” of Nineveh. The ancient remains of Nineveh, near Mosul, Iraq, situated between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, include the old ramparts that go around the city for 7.5 miles. It was an old city. The area was originally settled around 6000 BCE. It was “an exceedingly large city, a three-day’s walk across” (Jonah 3:3)—which is an exaggeration, of course. It’s the Bible’s way of saying that it was big—with a reputation.

Jonah had no desire to go there. He ignores God’s command, runs from the call, and escapes on a ship that then gets caught in a storm. The sailors blame Jonah, they assume that God is punishing them because of his sin. He offers to jump overboard. God provides a fish (not a whale), which becomes Jonah’s home for three days. Living in the smelly belly of a fish gives him plenty of time to think things over—and repent. Then, we’re told, Yahweh “spoke to the fish, and it spewed,” literally, vomited— “Jonah out upon the dry land” (Jonah 2:10). All of this happens in chapters one and two of Jonah.

Then we have in 3:1, “The word of the LORD came to Jonah a second time,” which leads us to think that the story continues. But not really. Scholars have shown that chapters one and two are one story; chapters three and four are an altogether different story. The link between them is Jonah and Nineveh and the persistence of God’s call to Jonah the prophet.[1] In the second story Jonah willingly goes to Nineveh, but there’s a new challenge. This time he’s not swallowed by a fish, but swallowed, as it were, by this “great city”—and eventually swallowed by grace. What happens there both surprises and infuriates Jonah. For he has much to learn about being a prophet, he has much to learn about the nature of God.

Stay close to the text, for things are not what they seem. Yahweh says, “Get up, go to Nineveh, that great city, and proclaim to it the message that I will tell you” (Jonah 3:2). So Jonah goes to Nineveh. He enters the city, walks all day, and then cries out to the wicked city, “Forty days more, and Nineveh shall be overthrown” (Jonah 3:4)!

But Jonah completely misjudges the situation. He makes assumptions about the city, and about God. What Jonah doesn’t know is that while this city might have a reputation, this exceedingly great city is great to God. In Hebrew, being “great to God,” suggests divine ownership, divine favor, and divine presence. God has different plans for the city of Nineveh.

Jonah was sent to proclaim a message from Yahweh. But did you notice that Yahweh never gave him a message? Jonah begins to speak, but is it really the word of the Lord? This word of warning, assuming God’s judgment and complete annihilation, is Jonah’s, it’s not from God. But the people of Nineveh believe his message—his false message—nevertheless! And, then, to his utter amazement and disappointment, the entire city proclaims a fast, its citizens put on sackcloth, and they examine themselves—they take a deep, honest look at their sin. They do all of this because the people “believed God.”[2]

Then the king hears what’s going on. He, too, puts on sackcloth and sits in ashes and examines his sins and the sins of the people. He joins the people in a public act of repentance and confession, acknowledging the sins oppressing the people, sins which they believe anger God. As king, he’s concerned for the welfare of the kingdom, he does what is best for them. He wants to identify the evil within himself and among them. He’s not afraid to name evil as evil. Everyone must fast, including fasting from water. Even the herds and flocks need to repent. They, too, shall not drink; they, too, must wear sackcloth. I’m not sure what the animals did wrong, but obviously they need repentance too! Humans and animals, together, enter a time of corporate confession.

The king puts all of this in a formal proclamation and says, “All shall turn from their evil ways and from the violence that is in their hands. Who knows? God may relent and change God’s mind; God may turn from God’s fierce anger, so that we do not perish” (Jonah 3:8b-9). Who knows? The Hebrew is actually closer to, “God may relent and change God’s mind…God may relent from the burning of his nostrils.”

In verse 10, we read, “When God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil ways, God changed God’s mind about the calamity that God had said he would bring upon them; and God did not do it.” This is confusing, I know, because God never says God will bring calamity upon them; those are Jonah’s words. And it makes it look as if God, like Jonah, was really eager to judge and destroy them, but had a change of mind only after the people repented. But is this really how it works? Do we get to change God’s mind? Was God only motivated to change God’s mind, to repent of what God was about to do, because Nineveh got its act together? Is the moral universe really built on cause and effect? What about grace?

It’s complicated—scripture is always complicated. And the English language is part of the problem. Phyllis Trible, one of the great biblical scholars of our age, who taught Hebrew Bible at Union Theological Seminary in New York for many years, bemoans that both the NRSV and the NIV translations obscure what’s happening here. The people of Nineveh turn, repent, and change their ways, and God turns—but they’re not part of the same turning. This is critical. The Hebrew word used to describe Nineveh’s turn away from evil is not the same word used to describe Yahweh’s turn from judgment to mercy. “Although mutual acts by the Ninevites and God eradicate evil, they turn on separate verbs. In other words, God’s response comes on God’s terms.”[3] It cannot be forced or manipulated. As Jonah came to discover, God does not do evil—even when the people are evil and deserve judgment. God does not do evil.

So what does Jonah do when he discovers that Yahweh is gracious? We read, “…this was displeasing to Jonah, and he became angry” (Jonah 4:1). The Hebrew is even stronger, “and it was evil to Jonah an evil great…,” and “it burned him.” He’s burning up. Jonah’s furious. The story ends with Yahweh saying to Jonah, “And should I not be concerned about Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not know their right hand from their left, and also many animals” (Jonah 4:11)? Again with the animals. “…more than a hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not know their right hand from their left…”

Whoever wrote Jonah—and scholars have no idea who wrote it or where—had a sense of humor. The author is also a sophisticated theologian who offers a nuanced understanding of our relationship with God. We learn that God is concerned with people we least suspect are deemed “great” in God’s eyes. God’s ways are not our ways, so we must resist judging too quickly. We have to be very careful how we listen to those who speak on God’s behalf, because sometimes what is heard from would-be prophets is not coming from God, but from the prophet’s ego.

What’s particularly striking about this story is that we’re reminded of the importance of individual, as well as corporate confession. The people repent and then the king repents. The king repents and calls the people to repent. A good leader leads a people to acknowledge sin and wrong and evil, and not run from it or deny it or cover it up or make excuses or blame other people. A good leader leads with humility and fears the righteous judgment of God. This is why it is essential for God’s people, the church, to confess its collective guilt and sin, for its implicit support or endorsement of sin in the world. So, too, a people, a nation needs to confess its collective guilt and sins—both what it has done wrong as well as the good that it has failed to do. Sins of commission and omission.

Confessing collective or national guilt or sin is almost unheard of these days. But it’s essential, really. We will never heal and move into the unfinished work of American democracy, as poet Amanda Gorman reminded us at the Inauguration in her poem “The Hill We Climb,” until we step into the past and repair it—repairing requires repentance, making the turn.[4] We need to acknowledge—we need to name, say, and confess the national and corporate sin of racism and white supremacy in our past and in our present, as these were among the motivating factors of insurrection at the Capitol several weeks ago.

During the Civil War, President Lincoln called several national days of prayer and fasting. President Biden, on Tuesday, standing before the Lincoln Memorial, at the national COVID-19 memorial, said that in order to heal we must remember and that includes remembering and acknowledging the wrong that has been done by the nation’s failed response to the pandemic. The story of Jonah teaches us the importance of having people in leadership that truly care for the welfare of all God’s people, that’s their job, it’s why they are there. Thank God for leaders who place their actions and the actions of the collective before the light of God’s judgment. This might sound quaint or naïve, maybe, but it shows us just how far we have fallen in our age and how much work that needs to be done.

Confession is good for the soul. And so is repentance. Jesus actually praised the people of Nineveh because they were wise enough to repent and turn and change their ways (Mt. 12:38-41). Repentance was required for them to receive his words and his vision of the kingdom. And repentance, a turn is required of us if we as the church are really going to the church, a people that faithfully serves and lives into Jesus’ vision of love and mercy and justice for all people. Everything hinges on the turn.

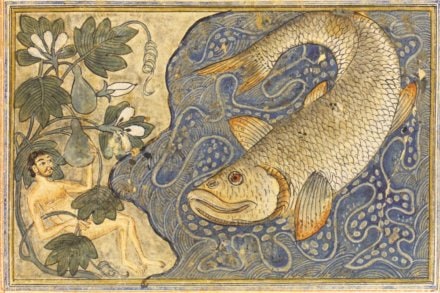

Jonah and the Whale (Persian, 14th century)

==================================================================================

[1] I’m grateful to Dr. Phyllis Trible, whose Jonah scholarship has informed my reading of the text, and this sermon. See Phyllis Trible, “The Book of Jonah,” in The New Interpreter’s Bible – Volume IV. (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1996), 463ff.

[2] Hebrew word for God here is Elohim, which is a plural noun, meaning “gods” or “deity.” In other words, it’s a generic word for God. The people of Nineveh believe in Elohim, a generic god, but not Yahweh—and it’s clearly Yahweh who sent Jonah to them, with a special word. This city doesn’t really know Yahweh, yet they are “great” and special to Yahweh.

[3] Trible, 514-515.

[4] Amanda Gorman’s poem “The Hill We Climb,” https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/20/politics/amanda-gorman-inaugural-poem-transcript/index.html