Sermons

Making Room for Doubt

April 16, 2023

For nearly two millennia, Thomas has been disparaged for his doubt. And for almost the same time, doubt itself has been disparaged in Christian life. It’s either one or the other, faith vs. doubt, for the Christian.

I can remember as a boy struggling with doubt. I heard that God wanted my faith. I was taught that doubt, being the opposite of belief, was something bad, something to be avoided and overcome. It was either faith or doubt for the Christian, never both faith and doubt. The presence of doubt was evidence that I didn’t truly believe, believe enough, have faith enough to be saved.

Our story in John seems to support this view. Thomas was away from the other disciples when they first encountered the risen Lord. For Thomas, it was too good to be true. So you can see why he was so skeptical. “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe” (John 19:25). I want to see the evidence. I want to see him. I want to touch his wounds myself.

Careful what you wish for. A week later, Thomas is with the disciples at home, again behind shut doors. Jesus stands among them again and said, “Peace be with you.” Jesus knows about Thomas’ incredulity. Jesus is there for Thomas—who was probably beating himself up all week for not being home when Jesus showed up the first time (I would have been). “Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt, but believe” (John 19:27). And then Thomas answered, “My Lord and My God.” “Blessed are those who have not seen,” Jesus says, “and yet have come to believe” (John 19:29). And, so, there it is. We can see how we’ve come to disparage doubt and desire belief. Belief is our consolation for not having Jesus’ wounds to touch. And who wants to be called a Doubting Thomas?

But is the criticism warranted? Is there really no place for doubt within the life of faith? Are they polar opposites? My own dualistic, either-or thinking on this subject began to collapse in a theology class, not in seminary but in college—a secular, public university in New Jersey, of all places. It started on the day I heard Professor Hiroshi Obayashi—a teacher I highly respected, a Christian—say, “We should always maintain a healthy agnosticism.” Humility of knowledge is essential. We need to live somewhere between faith and doubt, to be able to say what we know and what we don’t know and will never know. Slowly, I learned that doubt was extremely important in my life as a Christian. Not the doubt of the cynic or skeptic, but the kind of doubt that keeps things open, open to discovering something new and different, open to the possibility that what one thought was true might no longer be true or was never true and so you have to lean into a new way of knowing the world or yourself or neighbor or even God, a way that leads you deeper into truth. This is the kind of doubt that we need more of in the church—again, not the cynical, skeptical kind, that becomes tiresome—but the kind that leaves us curious and open. A holy curiosity. Doubt led Thomas to eventually say, “My Lord and my God.” It’s knowledge born of conviction. And conviction is born in the tension between faith and doubt. Doubt has a role to play; it, too, can lead us toward conviction. Doubt can lead us home. That’s why, years ago, I found myself saying in the invitation to the Lord’s Supper, “Come in your faith, and come in your doubt.” The Holy Spirit is at work in both. Doubt can lead us to the truth.

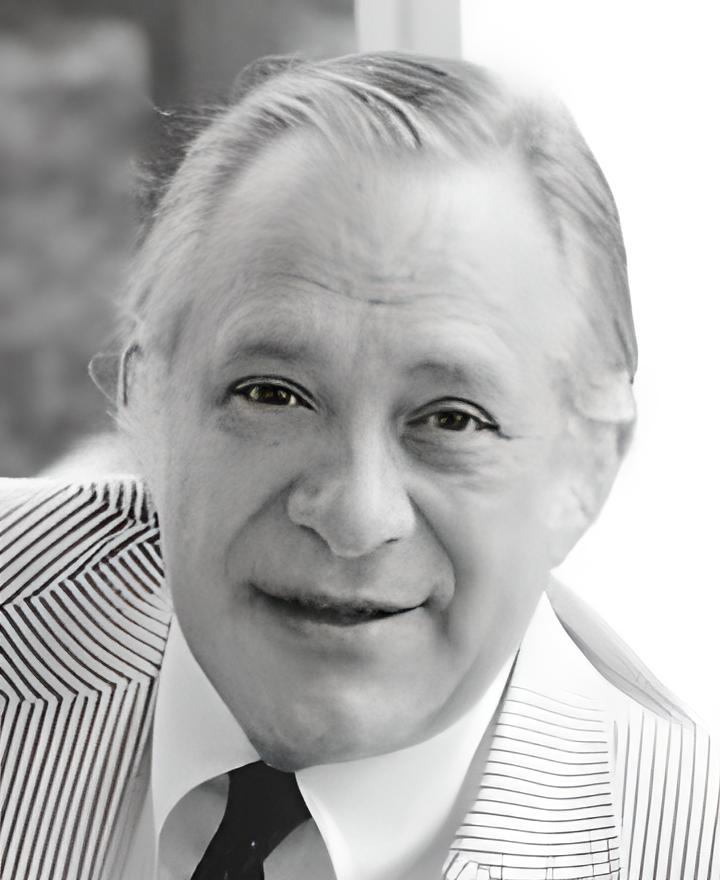

Thomas has much to teach us. It was James Loder (1931-2001), former professor of practical theology at Princeton Seminary, my mentor, and friend, who helped me see Thomas as someone deserving of our thanks. A little about Loder. He had an enormous influence on my life. Jim was one of the reasons I transferred from Yale Divinity School to Princeton. I took every class he offered, went to him for counseling (he was the first to encourage me to pay attention to my dreams), he gave the charge at my ordination, and, later, my doctoral dissertation was on Jim’s theology of the Holy Spirit. He was an extraordinary soul, brilliant, full of love, and you could see that love in his eyes.

In a short piece praising Thomas, Jim wrote, “It is to Thomas’ great credit that he knows a problem when he sees it… I see Thomas’ famous dubiety not so much a problem of whether [Jesus] lives, but if He lives—for that presents the problem. [Thomas’] doubt is rooted in a profound sense of the implications of such a claim and an unwillingness to take that step seriously.” “It’s a problem,” Loder says, “to have the presumably dead Jesus, radically reversing the universal tendency of matter to disintegrate, appear before you in a form of tangibility you’ve never seen before. It is a problem so great that it may violently awaken you from a deep Newtonian slumber [of cause and effect] and put you into the world in a new way—yet without any sense of direction…perhaps, all you know to do is wander off and go fishing.” For, Thomas “sees all too clearly that if [Jesus] lives, the apparent and assumptive world we have always tended to take for granted is not actually definitive of us after all.” [1]

Now, we could just say we believe and be done with it and go about our lives. This is what Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) called bad faith, “Just say you believe in God, then you won’t have to think about it anymore.” [2] There are a lot of people guilty of “bad faith.” Loder reflects, “Oh, yes, I know—‘Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe.’ Cynically, one can say, ‘Thank goodness he said that. I haven’t seen anything and I don’t want to, so I can say I believe, and by this saying, I can be better than Thomas and still not have it make any difference!”

But it made a difference to Thomas. It made a difference because his doubt and his search for proof were evidence that he actually cared enough to know the truth. The Hungarian-British philosopher and scientist Michael Polanyi (1891-1976), a brilliant mind who influenced Loder, said, “We know more than we can tell,” and that we come to know that something “more,” when we care enough to know. [3] As we saw in last week’s sermon, we come to know through love. [4] “Of course,” Loder suggests, “if Thomas had really wanted to avoid the implications of the claim his companions were making, if he had really wanted to avoid changing anything, he made a big, tactical mistake. He should have just walked away, left the scene so as not to be associated with a marginal person who thought that way.”

Thomas’ doubt was an expression of the investment he made in knowing Jesus, of how much he cared. Thomas had “the courage to say so, and the tenacity not to let go of it until he had an answer.” Thomas “believed the empirical test was necessary but found, like so many after him in all fields of human endeavor…that the truth always exceeds the proof.” And it’s the doubt that pushed him there. That’s because, as Loder said and as he knew firsthand in his own life, “Yes, sooner or later, when you get passionate about this you will walk headlong into the resurrected incarnation. When that stunning moment occurs or when that astounding realization gradually dawns upon you over a considerable length of time…when you say ‘My Lord and my God,’ without actually having to touch Him after all, you know you have been struck an immortal blow, you have been permanently wounded by the sheer awe and wonder of this grace. Once wised up, you can’t wise down.”

So, here’s to Thomas. Here’s to doubt. Here’s to being curious, courageous, and caring enough to pursue and explore and fathom what we mean when we say with conviction, “Christ is risen! He is risen indeed.”

James E. Loder (1931-2001)

Sources

[1] James E. Loder, The Transforming Moment (Colorado Springs: Helmers & Howard, 1989). All the references to Thomas are found in the Epilogue, especially 213-215. For more on Loder, see Kenneth E. Kovacs, The Relational Theology of James E. Loder: Encounter and Conviction (New York: Peter Lang, 2011).

[2] Cited in Loder, 214.

[3] Polanyi explores these ideas in his seminal work Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974), and The Tacit Dimension (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966).

[4] “Seeing is Believing,” April 9, 2023: https://catonsvillepres.org/sermons/seeing-is-believing/.