Sermons

Known in the Breaking

April 26, 2020

Third Sunday in Easter/ 26th April 2020

The lectionary readings for Eastertide are taking on new meaning this year. Last week, in John’s Gospel, we were with the disciples locked away in fear and with the questioning-faith of Thomas (Jn. 20:19-31). Today, we’re in the theological orbit of Luke’s Gospel that looks at the resurrection from a slightly different viewpoint. We turn to a story found only in Luke. Today we’re with two disciples walking on the way to Emmaus, a village about seven miles north of Jerusalem.

Ever since I was a teenager, I’ve loved this story—and it’s still one of my favorites. It’s shaped my faith and continues to inform my life. And as we come to terms with this pandemic, there’s something about this text that speaks to where we are at the moment. There are many things to say about these verses; there are many things this text has to say to us. But there’s one thing I want to zero in on, a theme that runs straight through Luke’s Gospel and is found here in the last chapter. It has to do with seeing and perceiving, cognition and recognition.

Two disciples are walking to Emmaus. We don’t know why. But it’s been a long day. Early in the morning they heard the news from the women who were at the tomb at dawn, news later confirmed by the others, that the tomb was empty: Jesus is alive, he has risen (Lk. 24:1-12). We find these two on the road engaged in a deep, long conversation, wondering, examining, revisiting the events of the morning, as well as the previous week, trying to figure it all out and hold it all together, trying to make sense out of it.

It’s then, “While they were talking…,” as most translations read, but it’s really more like, “In their talking….” From within their talking. In their searching and wrestling with the truth of their lives Jesus appears. But they don’t see him. Their eyes cannot perceive his presence. And here we have that Lukan theme: seeing and not seeing. At least four times in the Gospel (1:4, 22; 5;22; 13:7), plus two other times in Acts (3:10; 4:13), which Luke also wrote, we find this motif showing up. Why can’t the disciples see what’s right in front of them? Why can’t they see the one who walks beside them? Why can’t they see him? When we read the story there’s something in us that wants to say, “Why can’t you see the obvious?”

But, remember, Luke is a gifted storyteller. He’s not writing an historical account of what actually took place in Jesus’ life, but writing for a community of believers living fifty years after Jesus. When we remember that this Gospel, this story was written for all the people who would come after Jesus, written for Luke’s community, for the church, written for would-be followers and doubters and questioners, which means it’s written to you and me: Why can’t you see him? Why can’t you see the one who walks beside you right now? Why are you oblivious to God’s presence, unconscious of God’s desire to walk beside you, unaware of God’s craving to be near you, to enter into your space, to dwell where you live?

The disciples can’t see him, can’t see him through their grief and trauma and confusion. Grief, trauma, also depression, have a way of obscuring, distorting reality. It’s tough to see things clearly, to think clearly in grief or when overwhelmed by trauma or under the weight of depression. This is, in many respects, where we are at the moment. Whether or not we know someone who is sick or has died from COVID-19, we have heard the stories, we are surrounded by sadness and grief. Yesterday was the deadliest day in Maryland to date with 74 fatalities and it’s, of course, worse elsewhere. We can’t run from this reality. There are signs of depression and sadness in us, we’re cranky, running short on patience, we’re sleepless, restless, and having COVID dreams, when we can sleep. We’re caught in a collective trauma and we’re all in the same storm. Although—and we need to acknowledge this—we’re not all in the same boat. The storm is impacting each us differently, depending upon the safety and size of your boat. Some boats have been built with generations of privilege, others have not. Some have better access to healthcare than others, others do not. Still we are all in the same storm. In the chaos it’s difficult to see, to discern, to perceive, to know what’s going on and how God is mixed up in all of it. Where is God? How do we know?

The disciples listen to the stranger talking to them, they listen to his teaching, they try to make sense of the loss of their Lord. They’re enthralled by his presence and wisdom, but he remains incognito, elusive. They invite the stranger to dinner. They want to be near him more. He warms their hearts, the way he teaches and talks. But they still don’t see him.

And then the moment of “sight” comes, a moment of unveiling, when all becomes clear in a simple, subtle gesture, an embodied act. Assuming the role of the host, he takes some bread, and then blesses it, and then breaks it, and then gives it to his friends. There it is—the moment of insight. Of illumination. Of seeing. For Luke, that’s where we recognize the Resurrected One—in the breaking.

It’s only by grace that we see this. For me, this story is one of the keys of the kingdom, a key that unlocks a door that leads us deep into the heart of God, a story that helps us to see the hidden pattern or secret of the ages, that uncovers God’s preferred way of moving and acting in our lives, and unveils something at the core of authentic human life in the Spirit. To see the way Jesus moves through this story is to discover something about the nature of God.

If this is the way God is moving through the life of Jesus, and if Jesus is alive and alive within us, then this must become the way of God’s people. Take. Bless. Break. Give. That’s the pattern. It’s a cruciform pattern. The way of Jesus. Like him, we are to take or receive the gifts given to us by God (which is everything we have including our bodies, our lives), we are to acknowledge them as gifts that do not belong to us (nothing belongs to us). Then we bless them, meaning we offer them up to God with thanks, with gratitude. And then, the crucial stage, in love and gratitude we break them, break them in two or many pieces, we divide up what we have. Why? In order to give. We share our broken lives and our broken gifts, and we give them away in love. This is the rhythm of the Christian life alive with hearts that “burn,” warm hearts that feel alive when we live this way (Lk. 24:32). And it’s striking that this story took place in Emmaus, the only reference to this place in the Bible, which means “warm,” “warm springs,” or simply “hot.”

Take. Bless. Break. Give. But above all, Jesus was “known to them in the breaking of the bread” (Lk. 24:35). The crucial element is the breaking, and perhaps the most difficult. We’re happy to receive any and every gift God wants to give us, and we can be thankful for it. But if it ends there, then it’s not the way of Christ. There can be no giving, no true blessing, no sharing, we cannot become truly generous, our lives cannot participate in the life of the crucified Lord without the breaking, without the fraction, without the rending, without the sacrifice, without yielding and finally letting go. It’s in the breaking that they knew Jesus, because they recognized the one who was broken and they recognized in his breaking the willingness of God to be broken for the healing of the world. Jesus shares his broken body and his life with us, with you and me, with the world. The Resurrected One is always the Broken One. The Broken One is Lord and Savior.

In my walk as a Christian and as a minister, I believe, now more than ever, that the power and love and grace and presence of Christ are known in the broken places, perhaps only there. If not only there, then especially there. Christ is still known in the breaking. In broken bodies, broken hearts, broken people, where you are breaking, in broken places, broken families, broken lives, broken dreams, in people who are just plain broken, all broken by the world. This means that the church of Christ is most alive and faithful when we enter the broken places and bear witness to his presence.

In those broken places, we can only “see” that the life of God, the strength, the presence, the peace, the love, the courage, the hope, the light of God has a way of showing up and making an appearance and doing something unexpected that will warm our hearts and send us running back to Jerusalem. Back to the place of suffering and loss, but also the place of resurrection. We’re sent running into the world, not away from it, living from our brokenness, and giving ourselves, sharing our lives in love.

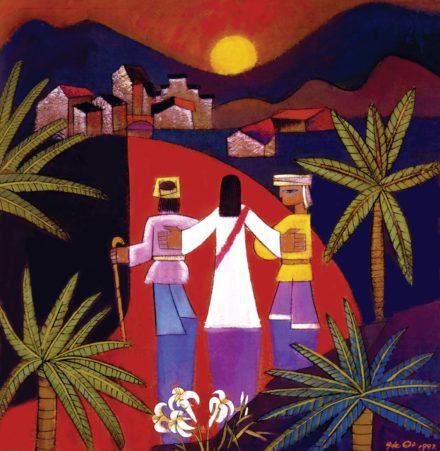

“Road to Emmaus” by Chinese-American artist Dr. He Qi.