Sermons

Just a Dream?

July 19, 2020

7th Sunday after Pentecost/ 19th July 2020

There’s more going on around us than we know. There’s more going on within us than we can imagine. That’s what Jacob discovered that night in his dream. Jacob, the selfish swindler, entered the world grasping for what wasn’t his, grabbing the heel of his brother Esau. He tricked his brother out of his birthright and stole their father’s blessing rightfully due to Esau. At this point in the story, Jacob’s a fugitive, running from Esau, running from God, running from himself. Alone. As day gave way to night Jacob gave himself over to his exhaustion. He crawled up beside a large stone and went to sleep. In that non-descript place Jacob slept. Some place. In this no-place, seemingly godforsaken place, this nowhere place, this wilderness place, Jacob was given a dream.

Given a dream. Jacob didn’t ask for or expect it. The Dream Maker gave him an image of a ramp (not really a ladder, but a ramp) that went from the ground and reached up into the heavens. The kind of ramp Jacob no doubt saw in Mesopotamia, ramps built along the four sides of a ziggurat, those terraced temples of Babylon, the top levels of which were known as the “gates of heaven.” The ramp is a busy place in the dream with God’s messengers going up and down, up and down it. While Jacob was sleeping, in the dream, Yahweh moved up over Jacob, poised over him as if whispering in his ear and said, “I, the LORD, am the God of Abraham your father and the God of Isaac. The land on which you lie, to you I will give it and to your seed. And your seed shall be like the dust of the earth and you shall burst forth to the west and the east and the north and the south, and all the clans of the earth shall be blessed through you, and through your seed. And, look, I am with you and I will guard you wherever you go, and I will bring you back to this land for I will not leave you until I have done that which I have spoken to you” (Gen. 28:13-15).[1]

When Jacob awoke, he quickly realized that was no ordinary dream. He could have rolled over and gone back to sleep (like most) and ignored the dream altogether. But he didn’t. My hunch is that he couldn’t. He couldn’t forget it and say it was “just a dream.”

Just…

Have you ever felt that the use of the word “just” can be such a “soul-crushing word”?[2]

Jacob couldn’t dismiss the dream. I have a hunch that it probably shook him and seized him and placed him before a power he had never really encountered before, a power, a God, he had heard about but never really experienced before then, a God who was, despite Jacob’s insecurities and devious traits, was somehow, for some unknown reason, on his side. On Jacob’s side.

Yes, sometimes we are given significant dreams. The psychiatrist Carl Jung (1875-1961) had a fancy name for these kind of dreams: he called them “big.” Big dreams come from some place deep and mysterious and shake our foundations and reorient our lives.[3]

When Jacob awoke, he knew that he was in no ordinary place. “Indeed, the LORD is in this place,” he said, “and I did not know. How awesome is this place. This is the house of God. Here is the gate of heaven” (Gen. 28:16-17). Filled with holy fear Jacob realized that the encounter in that place brought him up against the otherness of the Holy. Awe overwhelms him. He discovers that the land upon which he is standing is holy. This non-place becomes some place because in this place, and potentially any place, the Holiness of God can break through. I did not know the LORD was in this place. There’s always more going on around us and within us than we know.

Yahweh is closer than we think or dare to believe. Even though Jacob is running, he can’t run from God. Even though Jacob thinks he’s in charge of his life, he’s really a player in the larger drama of God’s plan and promise to provide a land and a future for all God’s people, and nothing Jacob does—selfish, scheming, swindler that he is—is going to stand in the way of God’s promise.

But Jacob is also more than a pawn in God’s cosmic scheme. God wants Jacob to know who he really is, and God wants Jacob to know who God really is. It’s a relationship. God’s promise includes Jacob. This means Jacob can stop running because his life means more than his self-absorbed preoccupations, more than all the guilt and the fear and the shame of his past. He can let it all go. Jacob’s life has cosmic significance. If he would just relax and stop running, he would discover that.

In fact, Jacob discovered that Yahweh is very close. And Jacob discovered that Yahweh likes to appear in surprising places, making mundane places holy. That’s why I’m repeating the word “place” so often, because the text does, six times. The Hebrew word for “place” here, maqom, later became one of the names of God in post-biblical times. Rabbis said that God is to be understood as place, a place that encompasses the world.[4] This suggests that any place has the potential of becoming the place where we encounter the Holy One. God is not limited to sanctuaries or temples or churches. “Know that I am with you and will keep you wherever you go” (Gen. 28: 15).

Any place can be the place where we encounter the holy. I often think that inside a CT-scan or MRI machine must be one of the holiest places in the world. Think of all the prayer that is offered there, of people searching for and experiencing God’s presence there. Or a COVID-19 intensive care unit. Or consider the garbage dump outside the walls of Jerusalem—otherwise known as Golgotha—a place of execution that became the place where God’s suffering love was seen on a cross. If God can be present there, then God can be anywhere. There’s always more going on around us “out there” than we know, as well as “in here,” within the psyche.

Just as there are geographical places that convey the Holy, that allow us to engage in heaven-to-earth, human-divine conversations, scripture tells us there are also internal, psychic places that are like those ramps, where heaven and earth converse, where we receive a divine word of promise and hope and assurance that directs our steps and waking moments. A dream is like a ramp between two worlds, between the unconscious and the conscious. As Jacob discovered, and countless others after him, the dream, itself, can become a ramp between heaven and earth, through which God speaks—speaks to us when we are silent, when our ego-defenses are relaxed, when we sleep. An even greater number, sadly, overlook, ignore, or discount the way dreams operate in scripture. “We have forgotten,” C. G. Jung said, “the age-old fact that God speaks chiefly through dreams and visions.”[5]

Now, to be clear, every dream is not from God (thank God!), but every dream has meaning, multiple meanings, and is given to us as sheer gift for the purpose of health and wholeness. No dream is given just to tell us what we already know but to tell us something we have forgotten or need to know for our well-being, to move us along life’s way and send us where we need to go. And sometimes, as Jacob knew, God speaks through our dreams. When that happens, they become symbols of grace. More than “just” dreams—they have power, and when used by God, they have extraordinary power to redeem and help make us whole.

But how do you know God is speaking through a dream? I’m not going to give you a checklist. All I would say is, you’ll know. You’ll feel it. The dream won’t let you go. Somehow, some way, you’ll know that you have to listen to the dream, and you know you have to live with and from it. For more than thirty years I’ve recorded my dreams. Over the years I have had three or four in which I know beyond a doubt God was speaking to me. They were significant, life-changing dreams that pointed me in a particular direction, and they continue to shape my life. Jacob’s dream radically changed his life, it moved him in the direction of healing and reconciliation and wholeness and paved the way for his life to become a blessing for the world.

The South African novelist and travel writer Laurens van der Post (1906-1996) was fascinated by dreams. He believed that Jacob’s dream is “the greatest of all dreams ever dreamt.”[6] Van der Post met Jung in 1949 and they become fast friends. Van der Post believed “a dream is the instrument of creative change.”[7] In a fascinating interview with the Bushmen of the Kalahari, one hunter said to van der Post, “There’s a dream dreaming us.” When pressed to explain, the hunter, deeply moved by his response, simply said, “I can’t tell you more, but there’s a dream dreaming us.”[8]

Van der Post gets to the heart of what Jacob discovered: “No matter how abandoned and without help either in themselves or the world about them, men [and women] are never alone because that which, acknowledged or unacknowledged, dreams through them is always by their side.”[9] And I would add, the one who dreams through us is also on our side. The One who dreams through us is with us and for us. And we can come to say of a dream, “Surely the LORD is in this place and I did not know it. How awesome is this place. This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.”

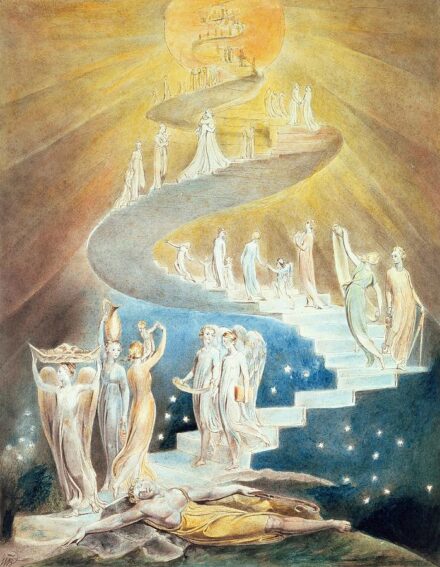

You see, there’s always more going on around us and in us than we know. What matters is that we connect with it, enter the fluid movement between heaven and earth, flow up and down on that ramp. I like the way artist William Blake (1757-1827) captured this movement in his rendering of Jacob’s dream.[10] (Many artists have painted this text. Do a Google search for images and explore and find one that speaks to you.) Personally, I love the way Blake’s image has steps, instead of a ladder, and a helix-like ramp, fluid with movement, with messengers of Yahweh moving up and down in a continuous, constant conversation conveying, translating heaven to earth and earth to heaven. It’s dynamic.

“Jacob’s Dream” (c.1805) by William Blake

And what if that ramp or ladder or helix or way goes straight through us?

I know this is a bold, maybe unsettling, claim, but the text leads us to these conclusions. My experience points in that direction. Someone is on our side. Jacob didn’t have to ask for help; it just came.[11] Jacob didn’t have a dream; he was given a dream and the dream had him. A dream that spoke so clearly to his situation—showing him what he couldn’t see for himself, that his life is worthy of God’s divine protection and promise. The dream offered him a future, granted him a telos, an end or purpose. He didn’t have to worry about his future, it would eventually lead him home. When Jacob realized this, it provided him with the assurance he needed to fulfill the meaning and purpose of his life. The dream was sheer grace.

Just a dream?

Just?

What do you think?

“Jacob’s Dream of the Ladder to Heaven” by Frans Francken (1542-1616)

=====================================================================================

[1] Robert Alter’s translation in The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004).

[2] There’s a scene in the movie Finding Neverland (Miramax, 2004), about the life of J. M. Barrie (1860-1937) author of Peter Pan, in which Barrie scorns the use of the word, “just” as “such a soul-crushing word.”

[3] C. G. Jung, “On the Nature of Dreams,” Collected Works 8 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), par. 554. “Significant dreams…are often remembered for a lifetime, and not infrequently prove to be the richest jewel in the treasure-house of psychic experience.”

[4] Taken from The Torah: A Modern Commentary, ed. W. Gunther Plaut (NY: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981). One rabbi said: “God is the place of the world, but the world is not His place.”

[5] C. G. Jung, Man and His Symbols (1953). See also C. G. Jung, Dream Interpretation Ancient and Modern: Notes from the Seminar Given in 1936-1941, edited by John Peck, Lorenz Jung, and Maria Meyer-Grass (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014).

[6] Laurens van der Post, Jung and the Story of Our Time (New York: Pantheon Books, 1975), 12. Jacob’s dream “remains,” he said, “the greatest of all dreams ever dreamt and the progenitor of all the other dreams, visionary material, and mythological and allegorical activity that were to follow” in the Bible.

[7] Interview with Laurens van der Post, “Dialogues with Sir Laurens van der Post.”

[8] “Dialogues.”

[9] Jung and the Story of our Time, 12.

[10] See Kathleen Raine, William Blake (Thames & Hudson, 1985).

[11]“For Jacob,” van der Post writes, “had not even to ask for help from beyond himself. The necessities of his being had spoken so eloquently from him that the dream brought him instant promise of help from that which had created him, henceforth to the end of his days, and of those who were to follow in his way after him” Jung and the Story of Our Time, 12.