Sermons

In the Presence of Mercy

October 9, 2022

Eighteenth Sunday after Pentecost/ 9th October 2022

On the way, along the way, the journey leads out beyond “home” to a new and different place. And it’s there, at a point between “home” and one’s destination, in this “region between Samaria and Galilee,” something happens. Galilee is home; it’s Jewish territory, a familiar place. Samaria is definitely not home for some. It’s an unfamiliar place for Jesus and his followers, and it’s not safe. It’s “unclean,” disturbing, alienating, unnerving. Yet, it’s here on the margins, in this “region between,” out there in a kind of religious No Man’s Land, where clean and unclean mix, out on the margins of society where the excluded and feared are sent to live and die, something holy occurs.

They saw him approaching the village. Forced to live in a ghetto, ostracized, cut off, they’re the first to see him. Keeping their distance, they cried out from the shadows, “Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!” They knew who he was. Word spreads. Miracle workers and faith healers were a dime-a-dozen in their day, but Jesus was different. What he offered women and men was different. His way was unique.

According to Luke, when Jesus “saw them,” he said to them, “Go and show yourselves to the priests.” Taking him at his word, moved by the power of his presence, of his mercy, trusting in the authority of his word, they go. Even before they’re cleansed, on the way, “as they went, they were made clean.”

Luke tells us they were lepers, which could refer to various contagious skin diseases. They were sick, a threat to the well-being of society, and so they were rejected, forced to live in isolation, cut off from their family and friends, alone. Out there in No Man’s Land, it didn’t matter if one was Jew or Samaritan. They shared a different stigma, a common stigma: they were unclean, not worthy of life in community. They would be welcome back if they could prove that they were cured and then ritually cleaned, certified by the religious authorities, and declared safe. That’s why Jesus told them to go to the priests, for the priests were the gatekeepers. The only way home for lepers was through the approval of the priests.

They head straight for the priests without even doubting Jesus’ skills as healer. The sooner they satisfy the priests, the sooner they’ll be home to their loved ones. The way Luke tells the story, it looks as if the lepers don’t discover their changed condition until they’re on the way. “And as they went, they were made clean.” Trusting his mercy and obeying Jesus’ commands, they go. And then something happens, the healing occurs, and then they’re cleansed. How do we know this? Because Luke tells us, “Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back….” They were healed en route; their healing was discovered on the way.

Ten are cleansed, one turns back to offer thanks and praise. We shouldn’t be too hard on the other nine. What would you have done? Eager, desperate to return home, back to loved ones and family, eager to leave the margins and enter back into the heart of society, return to normalcy. It does look as if they were ungrateful, that they used Jesus, took advantage of his power, took advantage of his mercy. You can appreciate Jesus’ frustration and disappointment. He gives and gives and gives and look what he gets in return.

Ten are cleansed, one returns thanks and praise, and that one is a Samaritan, this “foreign-born,” as Jesus describes him. He turns back. He’s grateful. The Samaritan gives thanks, which is the point here. However, Jesus is not simply commending him because he has good manners and remembers to say “thank you.” But there’s something else going on here. Go deeper.

“Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice.” The Samaritan. He disobeys Jesus, and he violates Jewish Law. He doesn’t go to the priests. He doesn’t go to the religious authorities. He’s a Samaritan; he’s not like the others. He’ll always remain unclean in the eyes of Jews.

At one point, he decides, he turns around, breaks free from the nine, and turns back to the source of his healing. At what point along the way, I wonder, did he realize that his heart was guiding him back the other way? And he didn’t go quietly. He goes with “a loud voice,” praising God for what happened to him. He doesn’t need the validation of the religious community to know he’s now clean. He doesn’t go with them; he wants to be with Jesus. He wants to complete the circle and return thanks to the giver of this gift. The gift—the healing and the cleansing—are not complete, are not real until he returns thanks to the giver. That he must do.

And so when he finally catches up with Jesus, he falls flat at the feet of mercy, prostrate, offering praise and thanks. Thanks! Yes, Jesus healed his leprosy, but more than that, Jesus gave him his life back, gave him a future. The healing of leprosy was one thing; we might even say it was secondary. Because through this healing he gained something else, he was “seen” as a human being again and then welcomed back into society. He was seen, by Mercy. He was noticed, by Mercy. He was recognized, by Mercy. And so, he returns thanks to Jesus, praising God.

And there’s even more going on in this remarkable text, and it’s easy to miss. Then Jesus asked, “Were not ten made clean? But the other nine, where are they? Was none of them found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?” Then he said, “Get up and go on your way; your faith has made you well.”

Get up and go on your way; your faith has made you well. You might be asking, I thought he was already healed? I thought Jesus healed them all “on the way” to the priests? Should the Samaritan take credit for his healing?

Ten were healed, but only one was declared “well”—the one who returned thanks and praise to God. It’s a subtle distinction being made here, but it’s important. It’s there in the Greek, but it gets lost in English. The word Jesus uses for “well” is the Greek word sozo, meaning “saved” or “whole.” It’s the only time “well” is used in the story.

Get up and go on your way; your faith has made you whole. What did he do to obtain this wholeness? His faith and trust, his praise and thanks, demonstrated to Jesus that he knew the true source of his life. The Samaritan is not whole until Jesus declares that he is. The Samaritan might have been healed, on the way to being cleansed, even welcomed back into society, but unless there is gratitude rooted and grounded in God and who God is, then one is not whole, one is not well, but still sick. We could say, then, that one can be sick and still whole because one’s identity, one’s being is rooted and grounded in God’s generosity and faithfulness. The presence of illness and disease are no barriers to feeling a sense of wholeness and completeness because this sense of wholeness is rooted in one’s relationship with God. The reverse is also true; one can have physical health but not be well or whole because the source of your life is not flowing from the one who is life and gives it freely, abundantly. It means you can appear healthy but still have a sick soul because you’re not grounded in the One who gives you life.

We are whole, becoming whole when our hearts are filled with gratitude for who God is toward us. We are whole, becoming whole when the meaning of our lives is rooted and grounded in God’s mercy toward us. Gratitude saves him. Gratitude makes him whole.

And with our wholeness, Jesus sends us on our way. Get up and go! The Samaritan goes with his wholeness, his wellness, back home to his family, community, village, and life. Healed in body, yes, but more than that, whole in mind, body, and spirit, with a grateful heart, he’s sent. Gratitude saved him; now, gratitude sends him. Gratitude made him whole; now, gratitude allows him to help others become whole.

And we miss the point if we think it’s only about physical healing. What Jesus is “seeing” and “healing” is the division in society and within people caused by disease, illness, and even ignorance. He doesn’t see a disease—leprosy—he sees people, women and men, who are trapped, caught, suffering, and alienated from God. He can free them from their disease, but he also offers a deep societal, systemic healing required for a people. This is what makes Jesus a unique healer and why he was different. What matters more, deeper than the physical healing, is the spiritual well-being, the psychological, emotional, and spiritual wholeness of God’s people.

And that wholeness comes in and through praise and thanksgiving, with and through a grateful heart, a life of doxology, a doxological life—which is not a bad way to live a life. It’s gratitude that sends and carries the Samaritan back to Jesus with a loud voice praising God. Praise is what makes us whole. The German theologian and mystic Meister Eckhart (1260-1328) said it best, “If the only prayer you ever say in your entire life is thank you, it will be enough.” Enough, indeed.

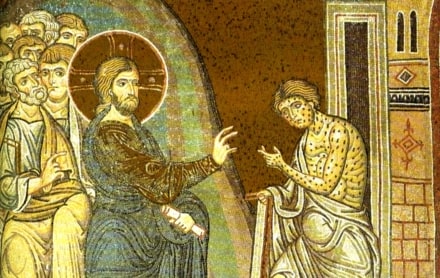

Twelfth-century mosaic, Cathedral of the Assumption, Monreale, Sicily.