Sermons

Beginning and End

July 7, 2019

Fourth Sunday after Pentecost/ 7th July 2019

Contemporary poet Stephen Dunn recounts his daughter’s experience at Vacation Bible School one summer. Dunn and his wife are suspicious of religion and faith, and not sure what to make of their daughter’s exposure to Christianity. In his poem, “At the Smithville Methodist Church,” he reflects on her experience:

It was supposed to be Arts & Crafts for a week,

but when she came home

with the “Jesus Saves” button, we knew what art

was up, what ancient craft.

She liked her little friends. She liked the songs

they sang when they weren’t

twisting and folding paper into dolls.

What could be so bad?

Jesus had been a good man, and putting faith

in good men was what

we had to do to stay this side of cynicism,

that other sadness.

OK, we said, One week. But when she came home

singing “Jesus loves me, the Bible tells me so,”

it was time to talk. Could we say Jesus

doesn’t love you? Could I tell her the Bible

is a great book certain people use

to make you feel bad? We sent her back

without a word.

It had been so long since we believed, so long

since we needed Jesus

as our nemesis and friend, that we thought he was

sufficiently dead,

that our children would think of him like Lincoln

or Thomas Jefferson.

Soon it became clear to us: you can’t teach disbelief

to a child,

only wonderful stories, and we hadn’t a story nearly as good.

On parents’ night there were the Arts & Crafts

all spread out

like appetizers. Then we took our seats

in the church and the children sang a song about the Ark,

and Hallelujah

and one in which they had to jump up and down

for Jesus.

I can’t remember ever feeling so uncertain

about what’s comic, what’s serious.

Evolution is magical but devoid of heroes.

You can’t say to your child “Evolution loves you.”

The story stinks

of extinction and nothing

exciting happens for centuries. I didn’t have

a wonderful story for my child

and she was beaming. All the way home in the car

she sang the songs,

occasionally standing up for Jesus.

There was nothing to do but drive, ride it out, sing along

in silence.[1]

Dunn confesses, “I didn’t have a wonderful story for my child.”

Story.

Stories are powerful, transformative, life-giving. We know their value all the more when we don’t have one to tell or when we can’t find a story that gives us life or when we’ve forgotten our story or when we’re frustrated with the stories we’ve been told that we want to find new ones. We each have a story to tell. We are shaped by our stories. We are shaped by the stories we tell ourselves—sometimes they’re true and sometimes they’re not. Sometimes people get stuck in false narratives, they get lost in someone else’s story, or they fall out of their story altogether. As we know, children love to hear a good story. Once upon a time…. Just say these words and we’re off to a world of fantasy and adventure. And the child in each of us still hungers to hear a good story.

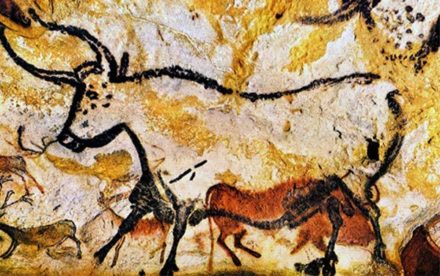

Human beings have been telling stories for millennia. Consider the cave art paintings of the Lascaux Cave in the south of France, estimated to be 20,000 years old. We’re not exactly sure what the images mean, but it’s clear that they are telling a story, conveying a message.

And story and faith go hand-in-hand. Where would be without the stories of the Bible? The stories carry the message; they drive the narrative of scripture forward. And not only is the Bible full of stories, scripture makes it clear that to be human means we are characters in the unfolding drama of God’s story of creation and recreation. We are embedded in a story that God is narrating through time, through us. By virtue of our baptism, we are engrafted into God’s still unfolding story of redemption, love, grace, and justice. As a result, it’s important, essential really, to value the storied dimension of our lives, to see, to know, to honor our individual stories—both the good and tragic dimensions of our lives—and the way they are caught up in the larger narrative of God’s story of salvation.

Christ said, “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end” (Rev. 21:6). Beginning and end, just like every story. We have the stories of Jesus. But scripture also suggests that Jesus is story. That is to say, in Christ our lives—our beginnings and endings—are found within the meta-story of God’s love. To know this means we are called to honor our unique, individual stories, knowing that our stories matter, they are integral to God’s sacred story that God continues to narrate.

It’s important for us to know this—really know this. Stories are serious business—extremely serious. Who narrates your life? Who has the power or authority to narrate your life? Who has the right to narrate your story? Human beings need to know that their stories matter, and that their lives are situated within a larger narrative or story or myth. By “myth,” I don’t mean something that isn’t true. Instead, a myth is the story of something that might never have happened, yet conveys a truth. In an age of scientism and literalism, we’ve lost the capacity to cherish myth. A myth is a deep story that tries to convey a deep truth. Such a myth or deep story grounds us and roots us, it gives us meaning, and purpose, which is why it’s extremely dangerous when individuals and people and even nations don’t have or have lost their myth or story. There’s nothing left to ground us.

I’ve just returned from attending seminars and lectures at the Jung Institute in Zürich. For the Swiss psychoanalyst C G. Jung (1870-1961), the most serious crisis of his life occurred around 1912-1913 when he realized that he was a man without a myth. Although he was raised in the Church (his father was a Reformed pastor), Christianity as he came to know it was flat and meaningless. After university, Jung became a world renowned psychiatrist, received fame and honorary doctorates for his scientific discoveries, he became a close associate of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), the world was his oyster. Slowly he realized that something was missing, life was hollow. He realized that that he no longer had a myth, a story to ground his life, one that offered meaning, which spoke to the existential challenges of being human in the early 20th century. So he went searching into the past.[2]

We need a story, a myth, to know that we are part of something larger than ourselves, a positive, life-affirming story. To live without such a story puts enormous pressure on an individual to create a meaningful life for oneself. The psychic strain of such a task can be overwhelming. In fact, one could argue that the rising mental health issues in the West (in Europe and in the U.S.), increased anxiety, depression, certain personality disorders are, together, a direct response to feeling rootless and disorientation experienced by many people these days, searching for meaning and purpose. It’s as if they’ve fallen out of a story and can’t find a new one. There was a time when religious faith, the richness of the Biblical tradition, the life of the Church offered such a myth, a story to root and ground us, to orient us and give meaning and purpose and hope. All of this has (and is) slowly shifting in the West.

So, what about us? What is this “wonderful story” of ours that still needs telling? I don’t think the Church tells one story. The story is Jesus and Jesus is the story of God’s love. But how do we tell this multi-faceted-gemstone-kind-of-story of ours? There are many aspects to it and we approach it from many perspectives and angles. There are plenty of great stories to shape the lives of our children, marvelous stories that enliven the hopes and dreams of our children. But what makes this story—our story—so different is the way it speaks to the why question and the who question. Who we are and why we are here. The story of evolution speaks to the how question, how we got here. The Bible’s story, including the opening chapters of Genesis, is less about how we came to be than why and for what. Evolution doesn’t love us. I don’t doubt the veracity of evolution, of course, it’s just that we have a different story. The creation story of Genesis was never meant to be a scientific text. It tells a different kind of story and answers a different set of questions. Our job in the Church is to speak to the why questions. Parents can tell their children how they came to be (all in good time, of course). But the deeper, more profound question that demands an answer, again and again, is why?—why do they exist? Why do we exist? Why do you exist? The answer to these questions requires a different kind of narrator.

The Bible’s story puts our children—and us—into the world, places us more deeply into this deeply disturbing and scary and terrifying, yet wildly wondrous and glorious and beautiful world. The Bible places our children and us into this amazing world with meaning, purpose, love, and grace. This story tells our children why they are here. The story gives them and us a song to sing and sanctifies our lives. Our children can’t discover this story on their own and neither can we. Someone has to tell us the story—again and again. We need to hear it. And someone needs to remind us when we can no longer remember the story.

It’s the story our souls crave to hear: to know that we are deeply and truly loved more than we could ever possibly imagine, that we’re not alone in this universe, that Jesus is present within us and among us, that we live in him, our Alpha and Omega, our beginning and our ending. Our stories are valuable, priceless, because they are contained in his story and his story is contained within the narrative of God’s redemptive love. And that’s a story worth telling.

Once upon a time…and in this time and the time to come until our time comes to an end and we are caught up in and consummated in the Life of the true narrator of our lives.

Lascaux Cave is a Palaeolithic cave situated in southwestern France, near the village of Montignac in the Dordogne region, which houses some of the most famous examples of prehistoric cave painting. Nearly 600 paintings have been discovered.

==========================================================================

[1] Stephen Dunn, New and Selected Poems, 1974-1994 (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1994), 183-184.

[2] C. G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), 170ff.