Sermons

Welcome the Prophet

June 28, 2020

Fourth Sunday after Pentecost/ 28th June 2020

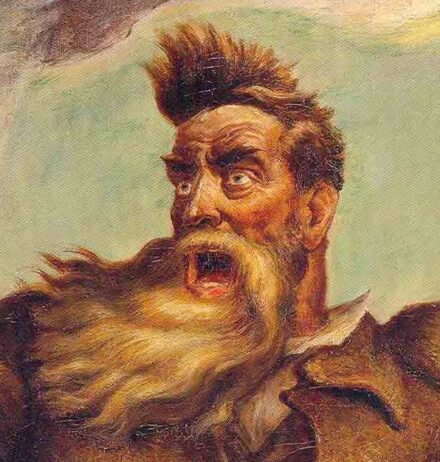

Prophet. What are your associations with this word? What images come to mind? A wild, wooly preacher of doom and gloom? John the Baptist preaching in the wilderness, “Repent! You brood of vipers!”? Someone like Nostradamus (1503-1566) who claimed to predict the future? Or maybe the fiery abolitionist John Brown (1800-1859) who raided the Federal Arsenal in Harper’s Ferry in 1859 to initiate a slave revolt.[1]

The prophets in the Hebrew Bible are often full of warnings. Jeremiah was known as the prophet of doom. Prophets make us uncomfortable. They’re loud and make a lot of fuss. They’re critical, adversarial, controversial. They’re always complaining about something. They’re rarely happy. They’re often considered losers, loners, outcasts, people who live on the fringe and seem a little odd. They’re usually not people we aspire to be or try to emulate.

And then there are false prophets, of course, with their own associations.

Have you ever heard someone say, “I want to be a prophet one day?” I haven’t. A psychologist might say such a person is gripped by a messiah complex or subject to ego inflation or suffers from unhealthy fantasies of grandeur, or, given what often happens to prophets, such a person might suffer from an unconscious death-wish.

So why then does Jesus command us to welcome them, listen to them? Because Jesus, himself, was a prophet, not only a prophet but one who stood in a long line of preachers who spoke with authority and conviction and became the mouthpiece of the living God. To welcome Jesus is to welcome the one who sent him and speaks through him.

From a biblical perspective, a prophet is one who speaks on behalf of God. In Deuteronomy, we hear, “I will raise up for [Israel] a prophet” like Moses, “I will put my words in the mouth of the prophet, who shall speak to them everything that I command” (18:18).

There are several things worth noting. First, one does not ask to be a prophet. One is chosen, called, even seized for the role. One doesn’t have a choice. Second, the message does not belong to the prophet, but to God. The prophet is God’s mouthpiece. The personality of the prophet remains, of course, God doesn’t take over his body and kick him out. Third, the prophet lives close to God, close enough to hear the heart-beat of God, close enough to know the heart and mind of God, intimately close enough to hear what God has to say, close enough to understand that Word, close enough to know that the message given is holy, and therefore a matter of life and death and that once heard, it must be said.

We can set aside, therefore, notions of the prophet predicting the future. The prophet does not predict the future, per se, but rather imagines the future. When the prophet preaches it’s always cutting edge and future-oriented, yet it does not predict the future. And the future vision always has a social dimension.[2] The prophet has a burden in his heart for people—widows, orphans, the poor, the weak, the most vulnerable, the child, the oppressed—and communities of people. Because the prophet, close to God, knows the heart and will of God, the prophet has been given a glimpse of what matters to God and what God hopes for, the prophet’s message will confront us with a choice: either welcome the prophet’s message, and embody God’s vision for creation and find life or ignore, reject, refuse God’s vision and deal with the consequences. The prophet, speaking for God, helps us to see the world as it is and then imagines what it shall be and calls us to live into that reality.

Because the prophet usually has a very good sense of the values and priorities of the prevailing culture, he or she also knows that hearing this message and living into this alternate future will generate considerable resistance and opposition. A prophet knows what a prophet is up against. She knows it won’t be easy, but she doesn’t have a choice. The prophet doesn’t have a choice. As Jeremiah knew, many tried to shut him up or expected him to be quiet. He, himself, tried to silence the word within him. “But if I say, ‘I will not mention [God] or speak any more in [God’s] name,’” that is, whenever I tried to withhold God’s message, Jeremiah said, whenever I tried to stop talking about God and God’s vision, God’s “word,” he just couldn’t do it because the word, he said, “is in my heart like a fire, a fire shut up in my bones. I am weary of holding it in; indeed, I cannot” (Jeremiah 20:9).

Jeremiah knew what every prophet and many preachers know: to deny that fire and refuse to serve it is to betray one’s soul and does enormous harm.

You see, a prophet—and even preachers now and again by God’s grace—have “received a window into the reality of God”[3] and know that view is so amazing, so extraordinary and beautiful, that if acknowledged and embraced, it has the power to transform existence and the world. As someone who has been drawn into the heart and mind of God, the prophet is never content with the world as it is. The prophet is always uneasy with the world as it is, the prophet can never be content with conventional wisdom and values and superficial existence and unjust social structures that do not reflect the heart and mind of God.[4]

We could say the prophet is more like a poet who, by grace, can imagine another world in this world, another reality waiting to be born, and, therefore, a different future.[5] Biblical prophets are like good poets who through the power of language give us the ability to go deeper into reality, they help us see things we would otherwise miss or ignore, things we don’t want to see, and then they transfigure the way we see with our own eyes and feel with our hearts. The nineteenth-century American poet James Russell Lowell (1819-1891) says it best. He’s not talking about being a prophet here, but it applies:

For I believed the poets: it is they

Who utter wisdom from the central deep,

And listening to the inner flow of things,

Speak to the age out of eternity.[6]

Because the wisdom, the voice and vision from “the central deep” of God—I love this—is so precious and holy and good, the prophet feels called, obliged, compelled to stand against everything in the world that obstructs God’s vision for the world. And God’s vision always includes righteousness and justice, which, by the way, does not mean getting even or vengeance. The words righteousness and justice are used throughout scripture to speak about God’s desire for healing, for wholeness, for relationships mended—with our neighbors, with God, with ourselves. If God’s desire for us is wholeness and healing, for things put right, then that means God is against everything that hinders this. It means that God’s heart breaks with every breaking heart—and it means our hearts should break too. God seeks to dwell in every place of brokenness—and God calls upon us, through the prophets, to go to the broken places too, and then do something about it. To offer compassion. For whom among us isn’t broken?

A true prophet comes to us in love to heal and reform. And in order for healing and reform to take place, for change to occur and reconciliation and even transformation, the prophet has to name the broken places, the prophet has to name the inequities, the places of injustice, and the prophet even wants to lead us into the brokenness, and feel the brokenness and pain, to see what is often overlooked or ignored and then do something about it.

When God’s message of justice (again, not vengeance) is heard and heeded it will inevitably clash with the prevailing powers because the powers that be generally don’t want to hear this message. And those powers are great and they’re sinister and demonic. That’s why prophets can appear controversial or adversarial. Prophets say things the majority doesn’t want to hear and because the majority has considerable power and influence, it does everything it can to silence, mock, ignore, and—if need be, even kill—the prophets to maintain the status quo, knowing full-well that the status quo, the way things are, withholds liberation, healing, redemption, wholeness for everyone. Yes, some experience these blessings, the majority, but not everyone. That’s why prophetic preaching in the church, especially today, is unpopular. It’s never been popular. And it certainly doesn’t grow churches because it’s not the preaching the masses want to hear. You can see why congregations get upset when pastors preach prophetically, and members complain that we’re being “political.” This is especially true in churches that are part of the status quo, churches supported by it, and benefit from things as they are.

You can also see why the prophet is often the voice of the minority and speaks from the margins, rarely the center (theologically or politically). Prophets are on the fringe—usually on the left, sometimes on the right. It’s tough to think, however, of a prophet, ancient or contemporary, who spoke from the center of society. I know they are there, but not many. I posed this question on my Twitter (@KenKovacs) feed this week: Name a living prophetic preacher or theologian who is white, that is, part of the dominant culture. I didn’t get a huge response. I was glad to learn about pastors and theologians, new to me, working prophetically from the edges of the church, less the center.

We need to find these voices and listen to them, learn from their experience, understand their vision, even if it makes us uncomfortable, especially if they make us uncomfortable. What voices do we need to hear? What voice do I need to hear? Who are the theologians that we need to be reading and learning from? Latinx pastors and theologians. GLBTQ voices. There’s the powerful prophetic voice of William J. Barber, working with Liz Theoharris, a Presbyterian minister, on the Poor People’s Campaign, both happen to be African American.[7]

Yes, there are things the church needs to hear, things we need to learn, especially white middle-class wealthy churches. And now that that the church is spending less time in a building these days, perhaps we can listen to what God might be saying outside the sanctuary, beyond the walls of the church.

Here’s an example. The Catonsville Youth for Black Lives Matter Protest was last Wednesday. More than a dozen CPC members were there. Some of our teenagers organized this youth-led event. All of the speakers were high school students. We heard poems and moving speeches that were prophetic, stating difficult truths about racism and institutionalized racism in our schools. Their words were honest and angry, naming the hurt and brokenness and making us uncomfortable. Such as, “White silence, white ignorance is violence.”

But these young prophets were also casting a vision, a vision for a very different future, a new world, of greater acceptance and understanding and reconciliation that we should welcome. We should welcome the voice of these prophets and others like them. And standing there, I found myself shouting inside—and should have said out loud—“Preach! Preach! Preach!”

May it be so.

John Brown from Kansan painter John Steuart Curry’s “Tragic Prelude” (1940).

==================================================================================

[1]On John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry see: https://www.nps.gov/hafe/learn/historyculture/john-brown.htm.

[2] Leonora Tubbs Tisdale, Prophetic Preaching: A Pastoral Approach (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2010), 1-4.

[3] J. Philip Wogaman, Speaking the Truth in Love: Prophetic Preaching to a Broken World (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1998), 3, cited in Tisdale, 4.

[4] Wogaman on preaching, Tisdale, 4.

[5] Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann, for example, often interchanges poet and prophet in his writings. See Finally Comes the Poet: Daring Speech for Proclamation (Fortress Press, 1989).

[6] James Russell Lowell, “Columbus,” The Poetical Works of James Russell Lowell (Boston: 1876).

[7] Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival https://www.poorpeoplescampaign.org/. See also the new book by Jack Jenkins, American Prophets: The Religious Roots of Progressive Politics and the Ongoing Fight for the Soul of the County (HarperOne, 2020).