Sermons

The Way of Mercy

July 10, 2022

My first real encounter with this text was when I was in junior high. It was at a presbytery youth retreat, in what was Newark Presbytery (NJ), where we reenacted the parable. For some reason, I was chosen to be the man who was robbed, stripped, beaten, and left for dead. The robbers weren’t too rough with me. But I was grateful for the good Samaritan who showed me mercy. I thought the lesson of the parable was that we should be nice to one another.

I know something now that I didn’t know then: this is more than a morality tale to elicit good behavior.[1] That’s not what parables are designed to do. Parables are short narrative fictions that refer to an external symbol; they point to something else. And that external symbol, for Jesus, is the Kingdom or Kin-dom or Realm or Empire of God. Parables are intentionally shocking. They’re designed to wake us up and turn us inside out to the reality of the Kingdom. They help us fathom the mysteries of God so that the truths they contain can enfold us, encourage us, and shape our lives. Parables pack a punch right to the gut of our complacency and dullness regarding the Realm of God. That’s what this parable does. It packs a powerful punch – especially to the lawyer, the rabbinic scholar who tried to test Jesus by asking, “What shall I do to inherit eternal life?” (Luke 10:25).

First, despite its appearance, this scholar of the Jewish Law (Torah) didn’t ask his question because he was confused about getting to heaven. He wants to be assured of the fullness of life that comes with God’s covenant with the Hebrew people. For the lawyer, the way to the life of God is by following the Law (Torah) in excruciating detail. He is obsessed with “getting it right,” he’s obsessed with perfection and ethical exactitude, and he’s afraid of getting it wrong. Around this time, there was a saying that “the study of the Law is of higher rank than practicing it.” This guy knows the Law, and his responses to Jesus are correct. But Jesus wants us to see that one can be technically observant, know all the answers, but be very far from the intent of the Law.

Jesus throws the question back at him, “You’re the expert, why are you asking me?” Again, the lawyer’s response is scripturally correct. He pulls from Deuteronomy (6:5) and Leviticus (19:18). God has a claim over every aspect of our lives – heart, soul, strength, and mind. We are called to love God from the depths; holding nothing back, we are to love God with energy, strength, inner resolve, and intellect. The lawyer knows the answer. It’s in his head. He knows the Law. He knows the facts – but he is lost and far from the Kingdom of God, as far as Jesus is concerned. It’s not enough to know these things – we have to do them. Live them.

So, who is my neighbor? That’s the tricky part. Society during Jesus’ time had strictly ordered boundaries – and you did not cross them. Society was hierarchical and patriarchal. There were Jews and then Gentiles – and Samaritans were in a class all by themselves. These were foreigners who were not expected to show sympathy to anyone. It was your religious duty as a Jew to maintain these boundaries all the time. It was about power. Your respect and care only extended to your tribe; you didn’t reach out to “those” people. Your “neighbor,” therefore, didn’t mean everyone because there are limits. Because many Jews at this time were anxious about keeping every aspect of the Law and trying to maintain the strict boundaries of their society, they wanted to know: What is the absolute limit required for me? Or, to put it a different way, what is the minimum I can get away with to fulfill the Law and no more?

The road from Jerusalem down to Jericho descends 3,300 feet over seventeen miles. It was a dangerous place, full of bandits. This unidentified man is beaten, stripped, and left for dead. The priest was expected to help – but he passed on the other side of the road. The Levite, the lay associate of the priest, saw him and passed to the other side. If the man was dead, the priest and Levite were obligated to bury him. Burying him would have made them ritually unclean for a time. It was easier to look the other way and keep going.

Then Jesus hits the lawyer in the gut. The next person to come along is a Samaritan – and it is the Samaritan who does what the Law requires; indeed, he does more than the minimum; he’s wildly generous. He exceeds the Law and ignores social boundaries. In offering this parable, Jesus was intentionally offensive. Sometimes that’s what it takes to wake us up.

From a Jewish perspective, Samaritans were not good people. Only a non-Jew could see a Samaritan as good. They were pseudo-Jews, subhuman. They were a ritually unclean people, descendants of mixed marriages with people of Assyria (2 Kings 17: 6, 24). This parable would have been earth-shattering and mind-blowing for the lawyer. It would have meant the collapse of his moral order. Shocking. He probably went away with a massive headache, dizzy, stunned, and in a daze. By depicting the hero as a Samaritan, Jesus demolished the exclusionary boundary expectations of his time that dehumanized people – and calls us to do the same. Social position and categories – race, religion, region, gender – count for little in the Kingdom. In a world with strict lines between insiders and outsiders, the Jesus movement sought to dissolve all these boundaries. It’s extraordinary. After these categories are stripped away, what’s left is the individual, a person like you and me in need. The neighbor, then, becomes, as Sören Kierkegaard (1813-1855) taught us, the one standing before or beside you, no matter who they might be. Your neighbor is everyone.[2]

Reaching across dividing lines, we show mercy because the other is worthy of love and respect. When we turn our attention to mercy and compassion, we have moved into the realm of God. This parable packs a punch because it allows us to fathom the divine mystery and tells us something about God, who reaches out across the great divide that separates us from God and shows mercy.

Ultimately, this parable is not a lesson in morality or how we must live to curry God’s favor, as it is a profound theological disclosure of the very depths of God’s being, of God’s nature. Jesus says this is who God is. If you want to participate in eternity, you must give up the ways you have thought about God. If you want to realize the promises of being a child of God (which is life eternal), then give up your childish ways of looking at God and think of God in this way. Jesus warns us that we’re far from God because our imagination needs to be re-ignited. If you want to participate in God’s life, you must re-envision your image of God. We must be open to the unimaginable.

God is like that Samaritan who reaches out for the victim and cares for the one left for dead along the side of the road. Jesus’ use of this image would have been scandalous – which is the point. God is like a Samaritan who will not walk on the other side of the road to avoid us. This is who God is – Yahweh, like the Samaritan, is not limited by destructive boundaries, nor does Yahweh act with a calculating heart, but is rich in mercy and free to show mercy and offers more than the minimum required. This is who God is. God is rich in mercy.

When we know that God is merciful toward us, when we have been on the receiving end of such mercy, like the man left for dead, we will know how to be merciful. There’s no other way. Mercy can’t be forced or demanded of us without it becoming a heartless ethical duty; it cannot be taught. Mercy must be experienced; it has to be received. This is the way of mercy. Our capacity to truly love our neighbor cannot be divorced from the wider mercy of God. Our love for our neighbor is an expression of God’s love for us. Our inability or unwillingness to extend mercy or compassion toward our neighbor says something about how we experience (or don’t experience) the mercy of God. Jesus is clear, here and elsewhere, that those who show mercy (and receive mercy) are living in the Kingdom, now. We don’t worry about rewards in an afterlife. We don’t get the Kingdom because we’ve been merciful. We get to live in the Kingdom when we know God is merciful. And when mercy is shown, we discover that the Kingdom is nowhere other than here. It’s the quality of life we receive when we know God’s mercy and reach out to one other with good and generous hearts. This is the way of mercy.

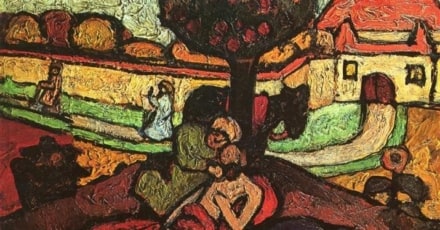

The Good Samaritan (1907) by Paula Modersohn-Becker (1897-1907)

[1] I am indebted to Thomas G. Long’s reflection on this text, “The Lawyer’s Second Question,” Candler School of Theology, News, Winter 2013.

[2] Sören Kierkegaard, Works of Love (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1964), 72.