Sermons

On That Day

December 8, 2019

Second Sunday of Advent/ 8th December 2019

The Second Sunday of Advent is traditionally given over to John the Baptist. He’s on stage this week. The spotlight is firmly placed on him out there in the wilderness of Judea proclaiming a word of warning. This week we make some space for this odd character. Not all the weeks of Advent, mind you, just one. “You brood of vipers!” is not the greeting we want to hear during the holidays. We can humor the Baptist for only so long, not unlike Advent. Who wants to hear, “Repent for the kingdom of heaven has come near” (Mt. 3:2) in December? And yet, the Church in its wisdom was wise to focus on John and his ministry during Advent, for he reminds us of something essential in us as we approach the birth of Christ. Repentance.

Repent. It’s a heavy word, laden with judgment. It’s true that John is full of judgment, he’s not happy that the religious authorities have arrived from Jerusalem to see why everyone was venturing out to the wilderness. They went to see the spectacle. But they were the ones John and his crowd were trying to avoid, were trying to wash away, suspecting that God’s judgment was about to be unleashed upon them any moment. They were arrogant with an inflated sense of themselves, incapable of bearing “fruit worthy of repentance” (Mt. 3:8). They put too much trust in the past, in tradition, in the way things have always been. But these are not are not going to the present or the future on the way. In other words, their minds were closed to God’s movement in the world.

“Repent” or “repentance” is the English translation for the Greek word metanoia used here, meaning “change your way of knowing.” A changed way of knowing, a turn, another way is needed because the current way of knowing is inadequate to what is coming. What is required in us and of us—all the time—in order to meet the advent of the Lord is change, meta-. Changed minds. Changed hearts. Changed eyes. Changed directions. Meta-minds; meta-hearts; meta–eyes, meta-direction. Change your ways for the kingdom of God is near. Clear the way. Prepare your heart. Prepare your mind. Prepare your eyes—because if you’re not paying attention you will miss the kingdom on that day, you will miss the advent of the Lord. What was true for John along the Jordan, is always true for us. It’s why theologian Karl Barth (1888-1868) believed that for the Christian: Advent is the only time.

What John is calling for is a shift in awareness. He’s calling us to pay attention, which is not as easy as we might think. N. Katherine Hayles, professor of psychology at Duke University, has done groundbreaking research on how attention works in us. There are, she suggests, at least two types of attention, both of which are vital in life. There is hyper attention and deep attention. Hyper attention is perhaps the oldest of the two, rooted deep in our collective memory, rooted in the need to survive, anticipating possible threats and sudden attacks, hoping to outrun predators and other dangers. Hyper attention is vigilant, we’re always “on,” nervously alert. “Hyper attention excels at negotiating rapidly changing environments,” Halyes explains, “in which multiple foci compete for attention.” We use hyper attention when we’re playing sports, such as football or soccer, or when we’re walking down a city street. Teachers use it all day in the classroom. Deep attention is the ability to focus on something without being distracted with knee-jerk reactions or assumptions. “Deep attention…is characterized,” Hayles explains, “by concentrating on a single object for long periods (say, a novel by Dickens), ignoring outside stimuli while so engaged, preferring a single information stream, and having a high tolerance for long focus times.”[1] Both are needed to live. One is easier to attain than the other, depending upon one’s temperament. Deep attention leads us into the depths, it’s similar to intuition, allowing us to see what is not immediately obvious or evident. If we’re easily distracted, closed-minded, close-hearted, blind, we will miss what’s in front of us and what is coming toward us.

The British psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist, Fellow at All Souls College, Oxford, has shown in his research that attention informs what we bring to bear on the world. What we give attention to, what we attend to actually changes what kind of things come into being for us. What we attend to changes us and changes the world. Attention matters.[2]

John the Baptist learned this from the prophets of Israel. He’s the descendant of a long line of seers, poets, visionaries who were attentive to the “new thing” that the Spirit of God is always about in the world and in our lives. “See, I am doing a new thing! Now it springs up; do you not perceive it? (Isaiah 43:19). As Matthew tells us, John placed himself within the tradition of Isaiah, who hundreds of years before could see what others could not see; who offered hope when others could only see judgment and pain and tragedy; who saw redemption and restoration in a time of exile in Babylon; who envisioned God at work in a new way during a time of political oppression and cultural alienation; who could see a future emerge in a place of destruction, decay, and devastation; who offered hope when there was no reason to be hopeful. A prophet who invited people to go deep, who warned us not to get distracted by things or become seduced by the surface appearance of things. Pay attention and you will see something begin to grow where you would never, ever expect or suspect it.

Look at that dead tree stump.

Go ahead, look at that dead tree stump. Look.

A shoot shall come out from the stump of Jesse, a branch shall grow out of his roots” (Is. 11:1). Out of dead places—or seemingly dead places—like a tree stump, a root will break forth, new life will emerge. Embedded in the heart of all things is a generative force at work to bring about a new future for God’s people. This “root” of Jesse is alive, its roots run deep, running through a special child of God upon whom dwells the spirit of God, “the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of counsel and might, the spirit of knowledge and the fear of the LORD. His delight shall be in the fear of the LORD” (Is. 11:2-3).

This one will perceive the depths of all things. He will go below the surface of things. “He shall not judge by what his eyes see,” Isaiah tells us, “or decide what his ears hear” (Is. 11:3b). Instead, righteousness shall be his guide and he will act on behalf of the poor, the poor who are so often overlooked, ignored, mocked, or judged just for being poor (Is. 11:4). He will hear their complaints, know their plight, he will hear their voices, he will work on their behalf—and therefore judge, condemn the people, the ideologies, the institutions that have brought about this inequity, who have withheld the poor’s rightful equity. He will come as the great equalizer on behalf of the poor, the vulnerable, the fearful, the lost. The root of Jesse will come when and where we least expect it, spring forth, take root in cold hearts, and offer a new world.

“Righteousness shall be the belt around his waist, and faithfulness the belt round his loins” (Is 11:5). And when he comes the world will be turned upside down, morality turned inside out. Therefore, expect the unexpected. Anticipate things to look ridiculous and foolish and zany and confusing and disorienting, even unnatural. “The wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard shall lie down with the kid, the calf and the lion and the fatling together, and a little child shall lead them” (Is. 11:6). When Isaiah wrote these words he was not imagining the birth of baby Jesus. He was not even anticipating a messiah. But he was looking for a child to lead the way into a new day marked by reconciliation and peace. A child is always the carrier of the future, an archetype of promise.[3] The prophet envisions a world that is fit for a child, safe for a child, a symbol of hope.

“On that day,” Isaiah says (Is. 11:10). He can see it. He can feel it in his bones. He knows what God intends for God’s people, for the world. “That day.” Not someday. Not one day. On that day. It will come. Centuries later, it was the first followers of Jesus, familiar with Isaiah’s writings, who looked back and read with fresh eyes and fresh ears the new thing God was doing in and through Jesus of Nazareth. Slowly, gradually the light begins to dawn on them. For those who encountered him, Jesus was that root, he was, is, the shoot, born to bring about a radically new future for God’s people, especially for the poor, the marginalized, the broken, the hopeless. He is God’s good news. And this also means, as John the Baptist knew, Jesus is bad news, because when he comes, everything changes. The high will be brought low; the low will be lifted up. The first will be last; the last will be first. Those who seek to save their lives must learn to lose them; and those who lose something of their lives will find them.[4]

The coming of Jesus always brings about a new age, a new day, a new season in our lives and the world. This means that the coming of Jesus always means the ending of something, an age, a day, a season in our lives and in the world. You can’t have one without the other. Didn’t Simeon say to Mary, “This child is destined for the falling and rising of man in Israel, and to be a sign that will be opposed so that the inner thoughts of many will be revealed—and a sword will pierce your own soul too” (Luke 2:34-35)?

A beginning and an ending; an end and a beginning. Falling and rising. Change. Repentance. Metanoia. Transformation. A turn.

We might resist the turn. Push against metanoia. We might be comfortable where we are, happy with things as they are, at ease. If we’re honest, there’s a little Ebenezer Scrooge in each of us. We’re always in danger of being too content in the lives we’ve created for ourselves, even if dark, oblivious to our hurts and wounds and the deep pain we carry with us and then project out upon the world, ignorant of the needs and wants of those who share the air we breathe. That’s why the Ghost of Christmas Past, who arrives for Scrooge’s “welfare,” Dickens tells us, for his “reclamation,” takes Scrooge back to his childhood, to the pain and sadness of his past in order to bring him forward.

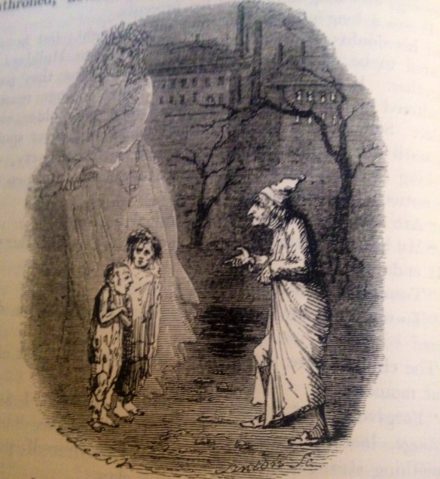

And there’s a scene in A Christmas Carol where the Ghost of Christmas Present shows Scrooge something significant, but only when he is finally open to seeing and hearing it. Scrooge learns that the Ghost protects in the folds of his robe two small children. Dickens describes them as “wretched, abject, frightful, hideous, miserable. They knelt down at its feet, and clung upon the outside of its garment.

“Oh, Man! Look here. Look, look, down here!” exclaimed the Ghost to Scrooge.

“They were a boy and a girl,” Dickens explains. “Yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish; but prostrate, too, in their humility. Where graceful youth should have filled their features out, and touched them with its freshest tints, a stale and shriveled hand, like that of age, had pinched, and twisted them, and pulled them into shreds. Where angels might have sat enthroned, devils lurked, and glared out menacing. No change, no degradation, no perversion of humanity, in any grade, through all the mysteries of wonderful creation, has monsters half so horrible and dread.”

Scrooge started back, appalled. Having them shown to him in this way; he tried to say they were fine children, but the words choked themselves, rather than be parties to a like of such enormous magnitude. “Spirit! are they yours?” Scrooge could say no more.

“They are Man’s,” said the Spirit, looking down upon them. “And they cling to me, appealing from their fathers. The boy is Ignorance. This girl is Want. Beware them both, and all of their degree, but most of all beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased.”[5]

Scrooge had nothing to say. Yet something was turning in him, taking root. He was waking up. He, too, has to repent—change his ways, in order to receive the Christ when he comes.

Ignorance and Want. The child of Christmas, the child of Bethlehem was born for these children—for these children in us—to bring about a safe world for them, and for us.

For a little child will lead them. A child continues to lead us.

Onward toward that day.

John Leech’s illustration of Ignorance and Want in A Christmas Carol (1843) by Charles Dickens.

John Leech’s illustration of Ignorance and Want in A Christmas Carol (1843) by Charles Dickens.

===================================================================================

[1] Cited in Maryann McKibben Dana, God, Improv, and the Art of Living (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2018), 70-71.

[2] Iain McGilchrist, Ways of Attending: How Our Divided Brain Constructs the World (London: Routledge, 2019). See also The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (New Haven: Yale University Pres, 2009).

[3] See C. G. Jung, “The Psychology of the Child Archetype,” Collected Works, 9, I (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977), par. 259-305.

[4] Luke 1:52, Matthew 20:16; Matthew 16:25.

[5] Charles Dickens, The Christmas Books/ Vol. I: A Christmas Carol/The Chimes, Michael Slater, ed. (Penguin Books, 1981), 108-109.