Sermons

Look Down

May 24, 2020

Seventh Sunday of Easter/ 24th May 2020

Last Thursday was the feast of the Ascension, the fortieth day after Easter. Ascension of the Lord is one of the oldest festivals of the Church, dating back to 68 A.D., right up there in importance with Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost. For many Christians throughout the world, especially the majority of Protestants, the day is completely overlooked. Celebrating Ascension Day was never part of my experience growing up a Presbyterian in North Jersey. Perhaps it was part of your faith experience, part of your tradition. It wasn’t mine. To be honest, I wasn’t all that liturgically minded, even after graduating from seminary. Ascension was not something I gave a lot of thought to.

Evidence of its one-time importance can be seen throughout Europe where Ascension Day remains a public holiday. I first became aware of this nearly thirty years ago. When I lived and served in Scotland, I was invited to travel with good friends to the south of France for two weeks, in early May. I remember it was a Thursday and we couldn’t figure out why everything was closed: post offices, banks, and schools were all closed. It was Ascension Day. It’s always on a Thursday. In France, Germany, Austria, Belgium, Norway, Ascension Day is a holiday.

But what is Ascension Day, and does it hold any real theological relevance for us today? Many would say, not really. It’s an odd story. The disciples are huddled together in Jerusalem. The Resurrected Jesus instructed them to remain there and wait for the promised Holy Spirit to come. The Spirit would bring them “power,” enabling them to be his witnesses in Jerusalem and “to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8). Then, just after saying this, and as they were watching, the clouds came down and lifted him up out of their sight. He ascended. Luke tells us, “While he was going and they were gazing up toward heaven, suddenly two men in white robes stood by them”—were these the same two men who appeared at the tomb on Easter morning (Lk. 24:4)? We don’t know. “They said, ‘Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven? This Jesus, who has been taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven’” (Acts 1:11). And the disciples don’t say a thing. But now the stage is set for Pentecost, for the coming of the Holy Spirit, at least according to Luke.

It’s an odd story. This past week there was a meme going around Facebook and Twitter that read: “Tomorrow is the feast of the Ascension. To those who wonder what it’s about, it’s the day that Jesus started to work from home.” A little coronavirus liturgical humor. But is it theologically true?

Sure, Jesus ascended from earth to heaven. So, we could say that Jesus is now “working” in heaven or the heavenly realm with God. But is this completely true? Has Jesus stopped working here? And is “heaven” really “home”? Is this world not also his home—or was it only a temporary home, a temporary dwelling? Scripture tells us that God took great delight dwelling fully, bodily in Jesus, in the life and body of a human being. Home is “here” too among mortals.

Theologically, we could say that with his ascension his humanity, which participates in and shares in our humanity, has now, with him been lifted up, brought into the heart of God. Christ ascended is the fully human-divine one raised up and into the life of God. Authentic humanity, human experience is now firmly grounded in God. Human life has become a place of divine visitation. Christ has taken human life and raised it up into the heavens, meaning into the dwelling place of God.[1] John Calvin (1509-1964) said that the Ascension tells us that Jesus rises to raise us into heaven, to overcome the distances between us and God and between one another.[2] And what we’ve come to see in and through Jesus is that God wants to be close to us and near us. Did not John discover this in his Revelation or Apocalypse when he heard a loud voice from the throne of God say, “See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be God’s people, and God himself will be with them; he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away” (Rev. 21:3-4)? God wants to be involved in our lives, God desires to dwell in the world where we live—now through the Spirit, now in you and me.

The Reformed theologian Jan Milič Lochman (1922-2004) once noted that Jesus’ “journey to heaven” becomes the disciples “journey to the ends of the earth.”[3] Ascension is less of an ending as it is a beginning. His ascent paves the way for the Spirit’s descent. His absence, as it were, invites us to step out into an unknown future; calls us to step up, step out, show up and be present as Christ’s people—and grow up into Christ’s mature witnesses to and servants of a love that seeks to transform the world.

“Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up toward heaven?” The disciples are watching Jesus ascend, fascinated by his aeronautical feats. But they have their heads in the clouds. Why do you stand here looking up? Get your head out of the clouds. There’s work to do here, where you live, right now. Look down.

This isn’t easy. We have a fascination with looking up and out, we’re enchanted and enthralled by what’s “up there,” what’s “out there,” and tend to avert our eyes from looking down and in. I’m not sure why we’re built this way.

Last Sunday there was a review in The New York Times of Alexander Rose’s new book, Empires of the Sky: Zeppelins, Airplanes, and Two Men’s Epic Duel to Rule the World. It’s a history of the fierce competition between the airplane and the airship early in the last century. Which one would rule the sky—the plane or the blimp? The skies were calling. German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (1838-1917) first became charmed by the thought of air travel here in the United States in 1863. The Count met a balloonist in the streets of St. Paul, Minnesota who offered him a lift up into the sky, a ride in a balloon that changed his life. In a balloon or airship “people felt untethered from the earth; many spoke about their experiences in over-the-top, rapturous tones.” One man said after an early balloon flight, “From now on our place is the sky!” “Such utter calm. Such immensity! Such an astonishing view,” people said.[4] The fascination with airships came crashing down, literally, with the crash of the airship Hindenburg in 1937 in Lakehurst, NJ. (If you search online, you’ll find eerie photos of the Hindenburg flying over Baltimore in May 1936.)

Why do you stand there looking up?

I’m reminded of the fiery song in the musical Les Misérables, a setting of Victor Hugo’s (1802-1885) novel about grace and love and the call for justice in the face of human suffering. The beggars of Paris are calling out, demanding justice and sing,

“Look down and see the beggars at your feet

Look down and show some mercy if you can

Look down and see the sweepings of the streets…

Look down, look down, upon your fellow man

Look down, and show some mercy if you can…

See our children fed

Help us in our shame

Something for a crust of bread

In Holy Jesus’ name

In the Lord’s holy name.”[5]

Not up in the sky. Not up yonder “in the sweet by-and-by.” Sometimes the Christian’s so heavenly minded we’re no earthly good. The follower of Christ is called into the world, not out of the world. Our focus is here. The Spirit doesn’t take us out of the world, but puts us more deeply into the world, down, deep into human experience, into human suffering and joy, like Jesus himself. The Christian life is not an out-of-body experience, but an in-the-body experience, one that, like Jesus, puts us deeper into our bodies, with a special sensitivity toward bodies, bodies that are suffering and ill, oppressed and weighed down, hungry for bread and dignity, broken and scared, and confronted by death.

In 1942-43, either just prior to or after the time of his arrest, pastor-theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945) having witnessed the atrocities inflicted by the Nazis upon the German people and the world, wrote out some thoughts about the direction the Church must take after the war. He said for too long we have looked at human affairs and the history of the world from high up, at the top, looking down, from the perspective of those with power and excessive wealth, from the perspective of the winners. But now we need to change our vantage point. We have “…learnt,” Bonhoeffer wrote, “to see the great events of world history from below, from the perspective of the outcast, the suspects, the maltreated, the powerless, the oppressed, the reviled—in short, from the perspective of those who suffer… We have to learn that personal suffering is a more effective key, a more rewarding principle for exploring the world in thought and action than personal good fortune.”[6]

The suffering of these days—and we are all suffering through this pandemic, whether directly or indirectly, and not all the same, but we are suffering—is calling the Church to get its head out of the clouds, and look down, to see the view from below, where people are hurting, because that’s where we will meet the risen Christ, that’s where the Spirit is sending us with the Spirit’s “power,”—power to love, to heal, to support, to fight, to care, to give

“In Holy Jesus’ name

In the Lord’s holy name.”

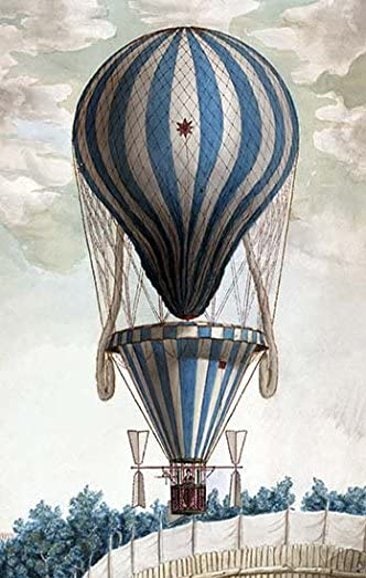

Air balloon “Ascension” (1828) flown by Francesco Orlandi throughout Italy.

=====================================================================================

[1] Willie James Jennings, Acts (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2017), 19.

[2] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (1559), 4.17.31.

[3] Jan Milič Lochman, The Faith We Confess: An Ecumenical Dogmatics (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984), 167, cited in Jennings, 19.

[4] Keith O’Brien’s review of Alexander Rose, Empires of the Sky: Zeppelin, Airplanes, and Two Men’s Epic Duel to Rule the World (New York: Random House, 2020), in The New York Times (May 17, 2020)

[5]Claude-Michel Schönberg, Les Misérables: A Musical. (London/Milwaukee, WI: Alain Boublil Music; Exclusively distributed by H. Leonard, 1998). Hugo’s novel was first published in 1862.

[6] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, “After Ten Years,” Letters and Papers from Prison, Eberhard Bethge, ed. (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co, 1972), 17.