Sermons

At Table

April 14, 2022

Maundy Thursday/14th April 2022

Tonight’s reading is part of an extended conversation Jesus had with his disciples around a Passover supper table. Jesus left the table to wash his disciples’ feet (John 13:1-11), and then he returned to the table to continue his farewell discourse. If we skip ahead in John’s Gospel to Easter, we find these words: “When it was evening on that day, the first day of the week, and the doors of the house where the disciples had met were locked for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you’” (John 20:19).

“They had gone back to the room with the table, their last gathering place. Thus, on the night of the resurrection, Jesus showed up there. With his friends. At the scene of the Last Supper. On Easter, Jesus goes from the tomb back to the table.” These are Diana Butler Bass’s observations from her blog essay, which she released earlier today, words inspired by a book she recommended several weeks ago on her blog and that I’ve been reading. The book is The Holy Thursday Revolution by theologian Beatrice Bruteau, which is the inspiration for tonight’s reflection.[1] I’m tempted to read the entire essay. It’s so good. Here’s a sample.

Bass observes, “If you are writing a play about [Holy Week and Easter], the scenes would be table, trial (with its various locations), cross, tomb (burial), tomb (resurrection), and table. The table is the first setting, and it is the final setting of the story. Indeed, when the disciples want to meet Jesus again the next week, they return again to the upper room to meet him at the table.”

“They never return to the cross,” she says. This is something, I confess, that I never noticed before. “Jesus never takes them back to the site of the execution. He never gathers his followers at Calvary, never points to the blood-stained hill, and never instructs them to meet him there. He never valorizes the events of Friday. He never mentions them. Yes, wounds remain, but how he got them isn’t mentioned. Instead, almost all the post-resurrection appearances — which are joyful and celebratory and conversational — take place at the upper room table or at other tables and meals. Table – trial – cross – tomb/tomb – table.”

All of which leads Bass, inspired by Bruteau, to raise this provocative question: what if the table is the point? This is the question that’s been swimming around in my head and heart these days.

“Every Holy Week,” she continues, “Christians move toward Good Friday as the most somber — and most significant — day of the year. Depending on your tradition, you may sit in silence, reverence a cross, listen to a sermon, recite the Seven Last Words, fast in quiet prayer. You may weep, sing mournful hymns, feel the weight of injustice. It is sobering business, keeping watch with the execution of an innocent man. For centuries, Christians have been told that everything changed that day, the cross was the bridge between the sinful world and the world of salvation. The cross is all that matters.”

“Somber, yes. The most somber day. Of course. But what if it isn’t the most significant? What if the most significant day was the day before — the day of foot washing and the supper, the day of conviviality and friendship, the day of Passover and God’s liberation?” Bass then asks, “What if we’ve gotten the week’s emphasis wrong?”

“Jesus loved meals. They knew that. They’d had so many together. Go back through the gospels and see how many of the stories take place at tables, distributing food, or inviting people to supper. Indeed, some have suggested that Jesus’ primary work was organizing suppers as a way to embody the coming kingdom of God. Throughout his ministry, Jesus welcomed everyone — to the point of contention with his critics — to the table. Tax collectors, sinners, women, Gentiles, the poor, faithful Jews, and ones less so. Jesus was sloppy with supper invitations. He never thought about who would be seated next to whom. He made the disciples crazy with his lax ideas about dinner parties. All he wanted was for everybody to come, to be at the table, and share food and conversation.”

Meals, suppers, the supper that we remember this night were all manifestations of the Kingdom of God. The meal was a symbol of God’s generosity, hospitality, and radical welcome. There wasn’t one supper but many suppers that inaugurated the inbreaking and real presence of the kingdom of God. Yes, it’s the Last Supper we remember this evening, the Last Supper of the Old World, the Old Order, and the first feast of the Kingdom of God that is both here and coming. Jesus gives us a table. And he extends to us a boundary-breaking invitation of radical openness, equality, reciprocity, and mutual indwelling, inviting us to participate in the life of God by participating in the life of the Son.[2] At this table, we come to see that the Lamb of God is our friend, a friend who becomes a servant, one who serves—he washes our feet (John 13:1-12), and he provides a rich feast, a meal of liberation, of exodus, out of the old way into the new way. “I give you a new commandment, that you love one another” (John 13:34). And no longer do I call you servants, but I call you my friends” (John 15:12).

This realization should shake us to the core! When we sit with this, our perceptions of ourselves and of God and of who we are in God are transfigured and transformed, and we realize that we, too, have been invited to sit at table in the Kingdom of God with our Lord, who is also our friend. Bruteau suggests that when we contemplate and really allow all that the table symbolizes and means to sink into our souls, yes, we will see Jesus as Lord – Dominus, in Latin – as well as something else. For Jesus has shown us that God is better named Amicus, meaning Friend.[3] And at the Lord’s table, our Friend’s table, we come to see our neighbors as friends, and we are formed and reformed into a new community that can change the world.

Let us hear the story tonight through the lens of Thursday. Let us come to the table as friends, the table of our Friend. For, yes, this is our Friend, our Friend indeed, in whose sweet praise we all our days could gladly spend.[4]

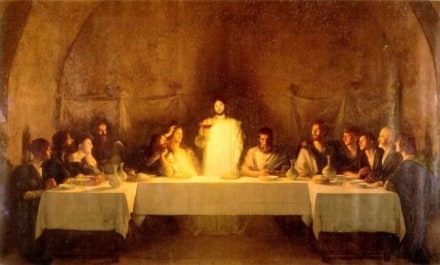

The Last Supper by Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret (1852-1929)

———————————

[1] Diana Butler Bass’s essay may be found here: https://dianabutlerbass.substack.com/p/the-holy-thursday-revolution?r=3gcwd&s=r&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=email&fbclid=IwAR1I76qPJbZCkjhgFTEtH7CJHzTFEkJKiYbN_GCGAm15JyX2J2BQOaHnztk. Bass’s essay was inspired by Beatrice Bruteau’s, The Holy Thursday Revolution (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2005).

[2] Bruteua, 63.

[3] Bruteau, 99.

[4] An allusion to the hymn, “My Song is Love Unknown.” Text by Samuel Crossman (1664) set to music by John Ireland (1918).