Sermons

A Homecoming From Babylon

February 5, 2023

Setting the stage

Well this is weird, isn’t it?

I don’t know what it was like the last time the office staff preached, but we’re going to figure this out together. And we’re going to trust that the Spirit is with us in this space. And we’re going to lean into what God is doing in this church and in our lives and in the relationships between us.

That’s a little bit of what’s in this text. The movement of God in places of uncertainty and new seasons. The movement of God within a community and a people who are desperate to come home. And the loud, resonant calling of God that is full of challenges and questions and promises and faithfulness.

My question for us today is this: “who are we?” Not “who have we been?” Not “Who will we be?”

“Who are we?”

Let’s turn to the Scriptures as we start asking this question.

We encounter the Israelites in an odd, peculiar moment, who might be asking this question without realizing it. They’re caught in a crisis of identity, of sorts, one that is mixed in a slurry of joy and disappointment.

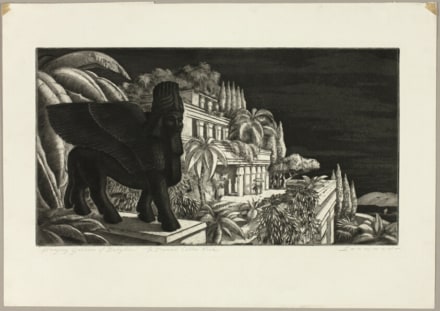

Today’s text is situated in the context of the Israelite’s return from exile in Babylon. The Book of Isaiah—which is really a few books, redacted together and sacredly stitched through time and tradition—the book gives us a bifocal view of the Israelite’s oppressive exile. In the first half, there are prophecies about the impending threat and violence of Babylon. In the latter half—the one we heard today—we hear oracles and hymns, poetry, and retrospectives. This latter half of Isaiah, is making sense of what has happened, and what will happen. [1]

The oracle we hear today in Isaiah is trying in part to make sense of why prophecy was not fulfilled the way it was expected. Why the darkness of advent waiting never gave birth to the epiphanic light of God’s deliverance.

Hold onto this context, and let’s trace this story.

The Israelites’ struggle

The Israelites return from captivity in Babylon. There is joy, of course, because of this wild, unexpected homecoming. For so long, they’ve grasped onto hope: “We’ll return one day. We’ll be back. Hold on, this isn’t the end.” And it finally came true.

So they begin rebuilding Jerusalem. They perform holy acts and restore sacred rituals. It is a revival of all that is supposedly holy and pure, a golden age of high praise. After being so hungry and forcibly deprived of ritual connection with God, what is happening isn’t only perceived to be right, it also feels right. “How could God be anything but delighted in these things?”

“Who are we?” They might have answered, “We are the children of Israel, the people of God, who received the law from Moses and who worshiped God in the wilderness. We are all of this: ceremony and sacrifice, covenant and law, obedience and prophecy. We are who we have been!”

We know from this side of the text, that though everything was so right, everything was so wrong somehow.

The Israelites came back from Babylon in the flesh. But in another sense, they never came back from Babylon.

Though there is so much joy in this moment, there is also so much loss. When the Babylonians broke the world, it never went back together the same way. The world came crashing down, and there was no way to fix it.

Something was nagging in the consciousness of the Israelites. “We returned to Jerusalem. We did everything right. We had fasts and feasts and rituals and built the city again. But something still isn’t quite right. Everything is fixed, but why doesn’t it feel that way?”

You and I, of course, are not the Israelites. But how could we not resonate with these feelings?

When God is not delighted with these fasts and acts, the question is “why?” Though we might be tempted to read anger and judgment into the voice of God in the Scripture, it might be something else. It might be grief, and loss. Mourning. God shares in the feelings of disillusionment.

Why is God aggrieved by the fasting and false trappings of holiness? The injustice and pride are certainly at the root of it. And there could be something else, too:

The Israelites are trying to live out their pre-Babylonian calling, which no longer exists. That world no longer exists.

God’s calling is particular, present, specific. God’s calling isn’t the calling of yesterday or tomorrow. It can’t be deferred and we can’t come back to it.

In the Scripture we have heard, God is drawing the Israelites back to who God knows them to be. Back to the image that God placed within their community: a people of justice, of mercy, of compassion, of liberation, of righteousness. Back to a source of life and identity planted deep within—like the one planted within us—from the foundation of the world.

God is drawing them back to the image and identity placed within them, and the calling that exists in the present. Not the calling of yesterday, before Babylon and before the world broke. The calling of today, the particular, present calling that exists in this terrible, beautiful world.

Everything else is besides the point.

“Who are we?” They are not the Israelites before Babylon, not the Israelites who hoped to be. Not the Israelites who were called yesterday, nor the Israelites called tomorrow. God is asking the Israelites to be who God knows them to be, today.

Our struggle

But we’re still not the Israelites. The Scripture we heard today wasn’t about us. After all, Presbyterians don’t have problems.

I don’t really know a poetic way to put this. We’re never returning from March 2020. We won’t ever be able to put the pieces back together. We won’t ever be who we were, as individuals, as families, as churches, as a country.

“Who are we?” We will never be the Catonsville Presbyterian Church of February 2020. Or the Michael of 2020. Or the Presbyterian Church (USA) of 2020.

For those of us sitting here in the walls of this church, we’ve “returned” from the isolation of the pandemic. But we’ve never really returned, in a sense.

For those in the church who aren’t sitting in these pews, who might still be living in isolation, the world may have “returned” without us.

And to make matters even more messy, even more complex, our faith demands more than living out our pre-pandemic calling. The calling of God to the Church is here in the present. It is particular to this community.

As some of you know, I’ve worked with an organization called Evolving Faith. The pandemic hit Evolving Faith hard, because it was just a conference at that stage. We’ve never really innovated as much as we’ve just floundered in the right direction. Recently, about a year ago, Evolving Faith launched an online space where people can gather, attend live events, start discussions, and share about their lives.

It wasn’t expected to do much, beyond hold some conference videos. But today, it has over 9,000 members. When I interviewed here, it was 8,000. Folks of every stripe—from Nebraska moms to disabled, queer Londoners—are wrestling with their faith, the struggles of their lives, the churches that they are leaving and joining. It’s a big, rowdy table, and people are finding a real sense of belonging and community.

The calling of God was particular, present. Evolving Faith didn’t know what the calling even was. But it wasn’t the calling of yesterday, the calling before the world fell apart.

God’s intervention

Let’s look back at the Israelites for a moment.

God asks the Israelites to loose the bonds of injustice, to bring freedom to the oppressed, and to give bread to the hungry. To bring light into places of emptiness. God is calling them back to the image of God—the imago dei—and to act as imitators of God—imitatio dei.

This is the path forward for the Israelites. God is restoring them by bringing them home to their identity and calling. God is saying, “Here is who you are.” “And because of who you are, here is what I am calling you to do.” Their homecoming dream—of mortar and stone, a majestic temple, and religious devotion—wasn’t what needed to be fulfilled. Instead, it was the very soul of their community that needed healing, attention, and renewal.

They needed to return to the question “who are we?”

And to do this, God called them to dismantle their way of life.

In order for the Israelites to follow the charge that God gives to them, the social order would need to be remade. It takes new ways of feeding ourselves to provide for the hungry. It takes different structures and policies to house the stranger and outcast. It takes new expectations and budgets to end the oppression of workers.’

These aren’t small things. But these are things that shape communities for the better, even though they are sometimes painful.

Our path forward

And what about us? What does a homecoming look like, when the world is still shattered? What does our identity and calling look like?

When I was in seminary, I studied with this kind, gentle-spirited man with an odd accent. I felt drawn to him and his courses, because there was nothing about him that seemed ambitious or egotistical. As it turns out, he was an architect of the Confession of Belhar and personally knew Desmond Tutu.

One time, this professor, Dr. Dirk Smit, paraphrased a bit of John Calvin. He said, “Where God is, humanity flourishes.” He continued, “And the inverse must also be true. Wherever humanity flourishes, God is there.”

That’s truth we can come home to, again and again. It’s a paraphrase of Calvin, but it’s also a paraphrase of this venture called the Church.

“Who are we, as the Church?” We are marked flourishing, by the liberation of Christ Jesus and souls that cry out for justice, mercy, feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, and making peace. This isn’t figurative. This isn’t some far-off hope. This is who God knows us to be.

It will take changes in the social order for us to live into who God knows us to be. We can expect it to be fun sometimes, and we can expect it to be rough or disorienting sometimes. But either way, it is faithful, and it is full of flourishing, whether we realize it or not.

When we deal with conflict face-to-face, that can be a way we come home to who God knows us to be.

When we have hard conversations about our differences, that can be a way we search out the calling that is particular to us today.

When we soften our hearts to collaborate with someone instead of winning, that can be a way we live out the charge that God has given to us as the Church.

The Table

When we gather at the Table, we practice all of these things.

That last supper—where Jesus and his disciples sat down for a meal—it was a profound moment of disorientation. The world was about to fall apart, only to be put together in a new way. The disciples, who walked with Jesus into hell and high water, were about to lose their teacher and friend. Jesus was about to endure betrayal, crucifixion, and death.

Paradoxically, this table is where the world would be remade, where we find a homecoming of sorts. It is where we are welcomed in our fullness, where Jesus beckons us to bring every part of ourselves: hopes, fears, prayers, and pains. It is where we ourselves are remade by the intimate, real, and special presence of Christ.

This Table is where we journey back to who God knows us to be.

There’s one last story I’d like to share. When I was coming out, I made this journey back to who God knows me to be. In the dimly-lit corners of an awkwardly-shaped chapel, a campus minister served me a chunk of bread and cup of juice. She was gay, too, and it was the first time I actually felt—deep in my body—what it meant to be loved and celebrated by God. In this profound spiritual experience, I discovered what flourishing really meant. I realized what the presence of God really meant.

I felt what it meant to come home to who God has created me to be.

What I discovered was that this Table is where one question matters, for you, and me, and this church, and all who are gathered around it.

At this Table—this place of spiritual homecoming—we ask and discover God’s response to the question that really matters, “who are we?”

Not “who have we been?” Not “who will we be?”

“Who are we? The Church; a people of flourishing; a people finding our way back home to who God knows us to be, today.”

[1] Jacob Stromberg, “The Book of Isaiah: Its Final Structure” in Lena-Sofia Tiemeyer (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Isaiah. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190669249.013.1